The word “Japonisme” used in this commentary is to describe the influence of Japanese art and craft on European artists mainly in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Note: The following sentences are excerpts from the narrations.

Audio controller

(♪) The Japanese archipelago lies off the eastern edge of the Eurasian continent. Mild in climate and with abundant rainfall, it is covered with steep mountains and abundant vegetation. The dark greens of densely forested slopes, the shifting monotones of mist-laden valleys, the rich browns of the earth—this was the palette that nurtured Japan’s diverse expressions of art.

“Pine Trees” Screen

By Hasegawa Tohaku.

National Treasure. Momoyama Period (16th century).

Tokyo National Museum. (Whole and partial views)

Image:TNM Image Archives

(♪) Ukiyo-e’s influence upon European impressionist painters is well known, but less familiar is its influence upon Western picture books in the late-nineteenth century, a time that coincided with the incipient period of woodblock printed color picture books in Europe. (♪)

Fifty-three Stations on the Tokaido: Hakone

By Utagawa Hiroshige

ca. 1833

Tokyo National Museum. Image:TNM Image Archives

The Nursery Rhymes

By Claud Lovat Fraser

1916

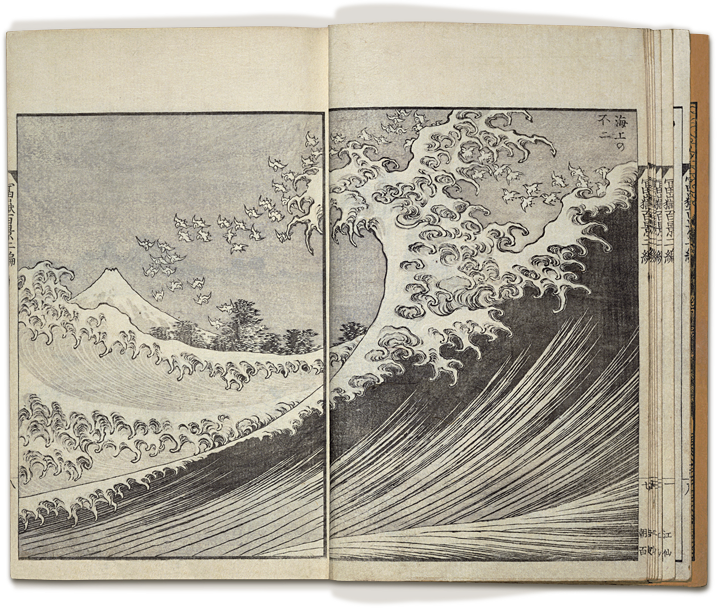

Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji: Fuji on the Ocean By Katsushika Hokusai

1835

Tokyo National Museum. Image:TNM Image Archives

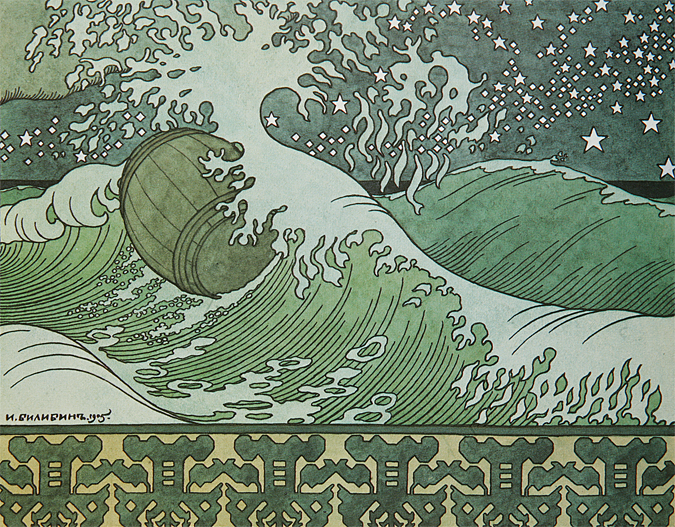

The Tale of Tsar Sultan

By Alexander Pushkin.

Illustrated by Ivan Bilibin

1905

Audio controller

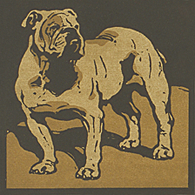

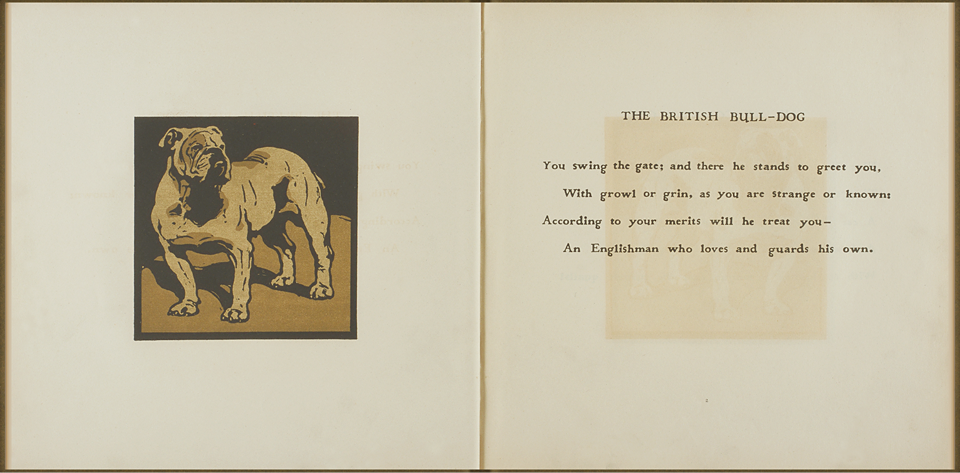

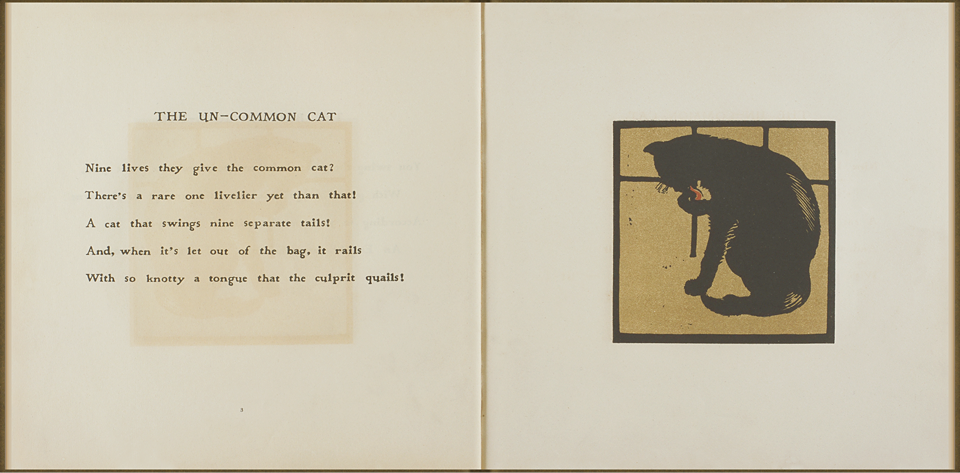

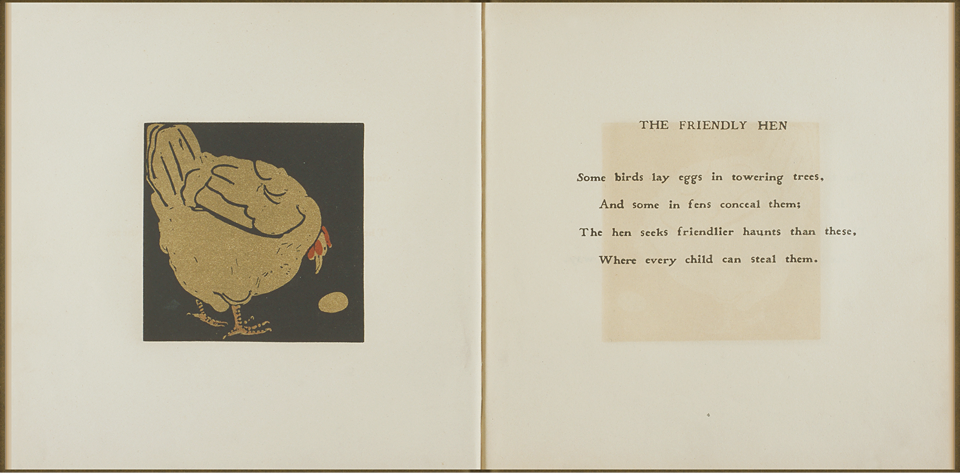

(♪) William Nicholson’s The Square Book of Animals reflects the universal aesthetic of Japonisme. In his pages, the familiar animals and livestock of daily life emerge as pure works of art. Here, breaking away from the conventions of chronological storytelling for picture books, he emphasizes the space and composition of each illustration. A well-calculated balance is achieved between the elaboration of individual pages and the overall composition of the picture book as a whole. (♪)

The Square Book of Animals

By William Nicholson. Rhymes by Arthur Waugh

1900(1899)

(C) by permission of Elizabeth Banks

Audio controller

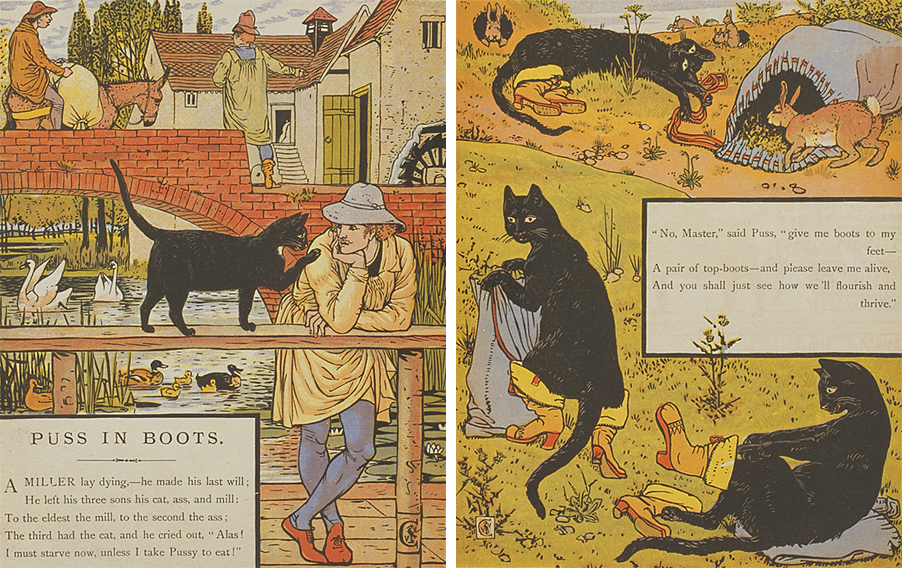

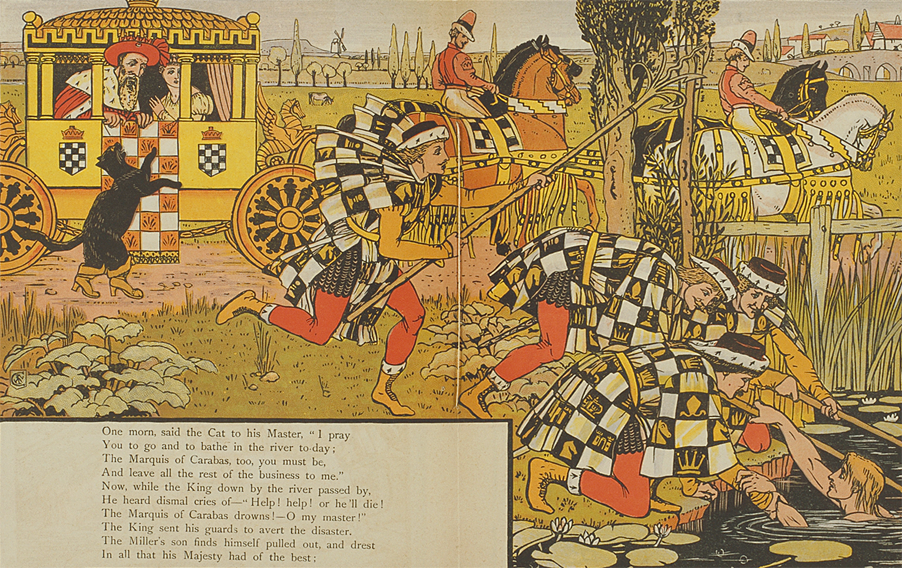

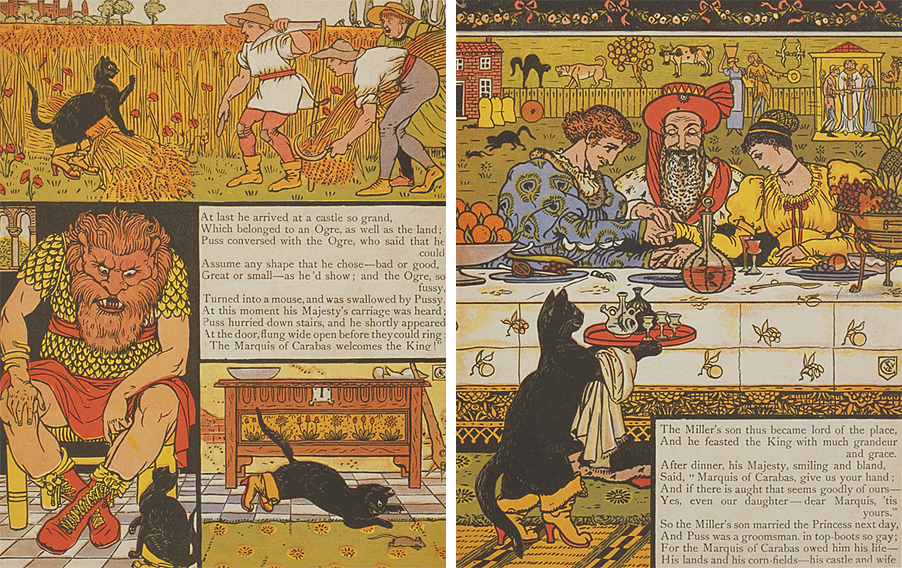

(♪) Walter Crane’s Puss in Boots depicts people and things in vivid colors and clear outlines. The book may seem quite different from Edo picture books, which were printed in monotone, but they have much in common in the treatment of space. Crane deliberately ignores the basic one-frame for one-scene rule of composition passed down since the Renaissance, filling each page with multiple scenes unfolding in succession, a composition similar to that of Edo picture books.

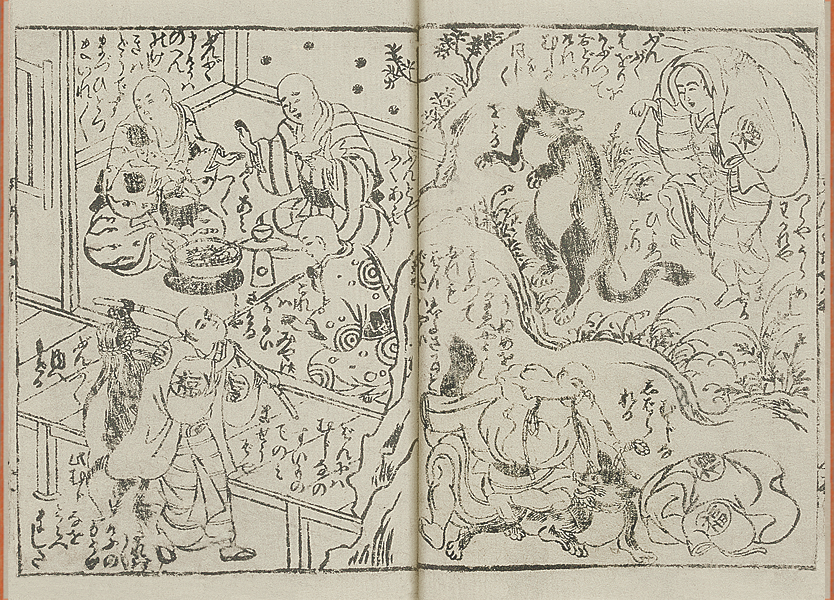

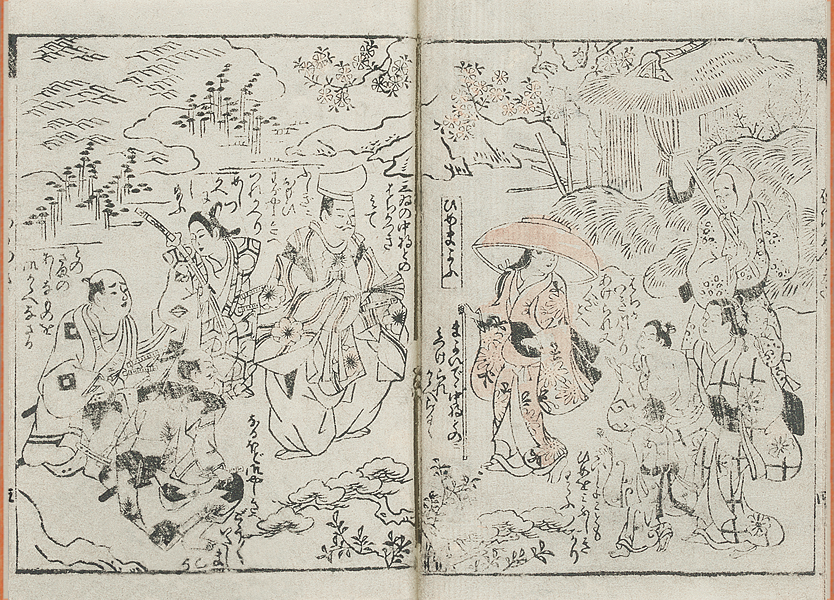

Edo Picture Book Bunbuku’s Teakettle

Edo Picture Book Princess Hachikazuki

Puss in Boots By Walter Crane

1875(1873)

(♪) Page 1 shows the first and second sons and their inheritance, and the third son, who received only a cat. (♪) Page 2 portrays in bold images the activities of the cat, which has promised it would make the third son flourish.

(♪) Pages 3 through 6 show the ingenious ways the cat devises to make the third son the Marquis of Carabas.

(♪) On pages 7 and 8 the cat sets out on a campaign to take away the ogre’s castle and put it in the Marquis’s possession, and then comes the grand finale.

(♪) In the mere eight pages of this picture book the spectacular performance of Puss in Boots is staged in bright colors and elaborate detail. (♪) An ardent admirer of Japonisme, Crane is said to have had woodblock prints by ukiyo-e painter Toyokuni in his collection.

Audio controller

Kanariya shakuyaku (Canary and Peony) By Katsushika Hokusai

ca. 1834

Tokyo National Museum. Image:TNM Image Archives

(♪) Japonisme also conveyed an aesthetic in which the entire world of nature could be appreciated within even its smallest fragment. Looking at some picture books in England, one experiences the momentary illusion that the flowers and birds from Hiroshige and Hokusai prints have somehow crossed the oceans to England to appear in those books.

We cannot fail to notice that these and other outstanding picture books came into being in the West at a time of contact with Japanese artistic expression. They are testimony to the enthusiastic response of Western artists toward the end of the nineteenth century to the exquisite forms of beauty to be found in art from distant lands. (♪)

Konjaku miken Shobutsu moko no shinzu (Fabulous Creatures of Past and Present)

By Kawanabe Kyosai

1860

Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum

The Story of Noah’s Ark Told and pictured by E. Boyd Smith

1905

Rigyo yuei zu (Swimming Carp) By Kawanabe Kyosai

1885-1886

Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum

The Water Babies By Charles Kingsley. Illustrated by Jessie Willcox Smith

1916

Kiji to hebi (Pheasant and Snake) By Katsushika Hokusai

ca. 1830-1833

Tokyo National Museum. Image:TNM Image Archives

Rumbo-Rhymes; or the Great Combine; A Satire

By Alfred C. Calmour; Pictured by Walter Crane

1911

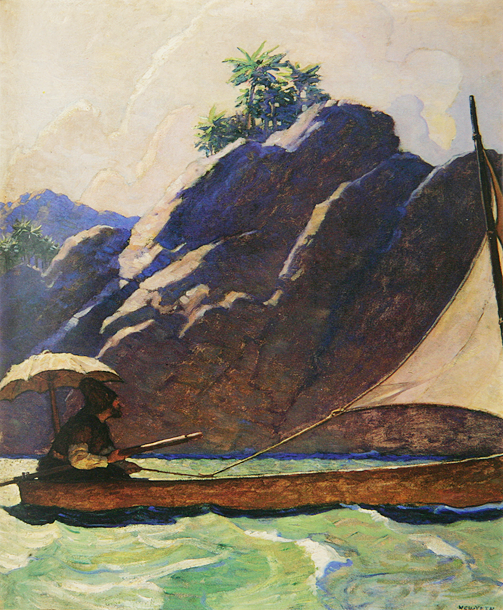

Robinson Crusoe

By Daniel Defoe; Illustrated by N.C. Wyeth

1920