Part 3 : Special Corners

Kenji Miyazawa: His works spread transcending national boundaries.

Beginning

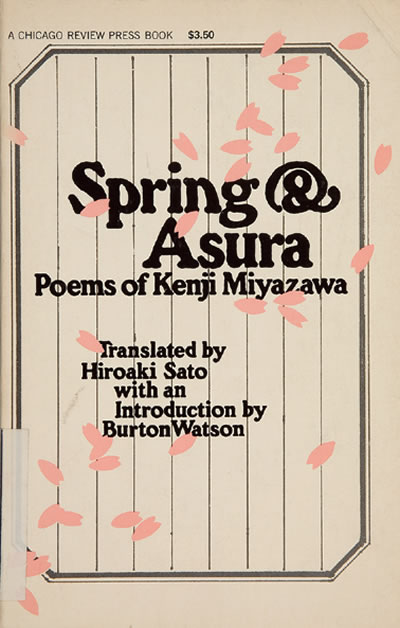

In September 1933, Kenji Miyazawa passed away, leaving behind many unpublished poems and fairy stories. Only two of his books were published during his lifetime: “Haru to shura” and “Chumon no ooi ryoriten.” Four months after his death, Shimpei Kusano published “Miyazawa Kenji tsuitou,” drawing public attention and leading to the publication of his yet-to-be-released works.

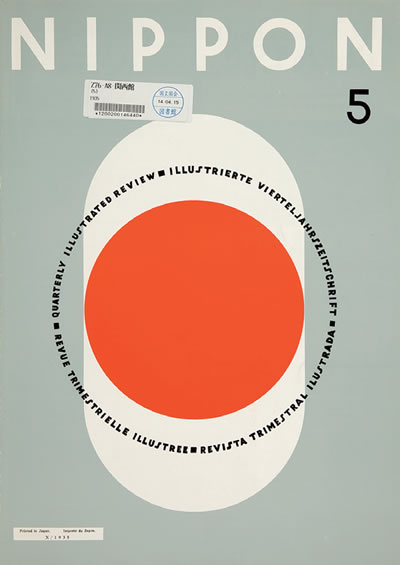

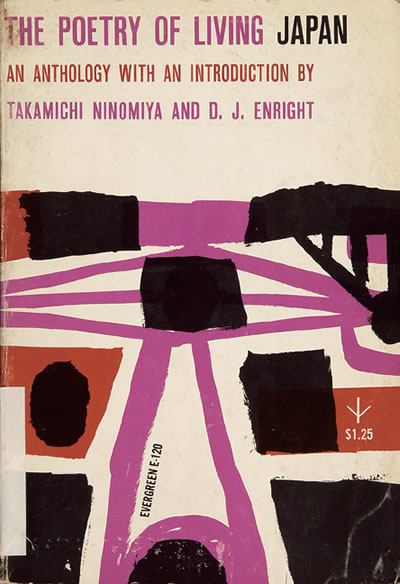

As early as 1935, the French translation of Miyazawa's short story “Yamanashi” was published in the Japanese external publicity magazine “Nippon” (No. 5). (No.267 is a reprinted edition.) In 1941, “Amenimo makezu" was translated in Beijing, followed by the translation of “Kaze no Matasaburo” in Hsinking (currently Changchun) in 1942, and those of “Serohiki no Goshu" and “Chumon no ooi ryouriten” in South Korea in 1961. In the English-speaking world, an anthology of Japanese poems (No.268) that contains four of Miyazawa's poems including “Sapporo-shi” was published in 1957. From 1960 to the 1970s, many poems and fairy stories written by Miyazawa were translated in foreign languages.

However, his works were not widely read in overseas countries until the 1980s, when foreign researchers who came to Japan and studied Japanese literature started to introduce Miyazawa's works to their home countries, eventually leading to the growing popularity and reputation of Miyazawa's works in many countries and regions.

Changes

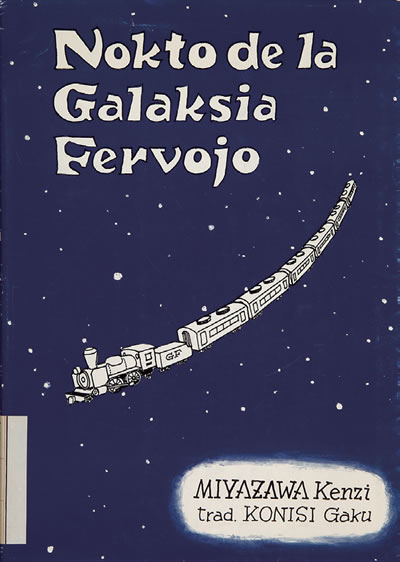

Kenji Miyazawa loved poems by Tagore and music by Beethoven, and learned German and Esperanto, aspiring to see the world with a broad perspective. He wrote many of his works inspired by the nature of his hometown in Iwate, while at the same time he also successfully created a unique fantasy world by incorporating foreign elements into his works. In some translated versions of his works, however, the exotic flavors of his works were removed and Japanese flavors added.

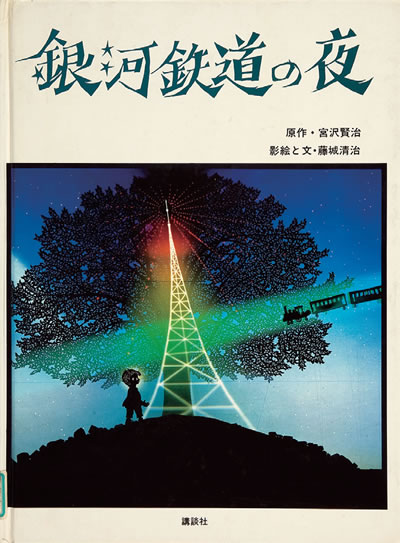

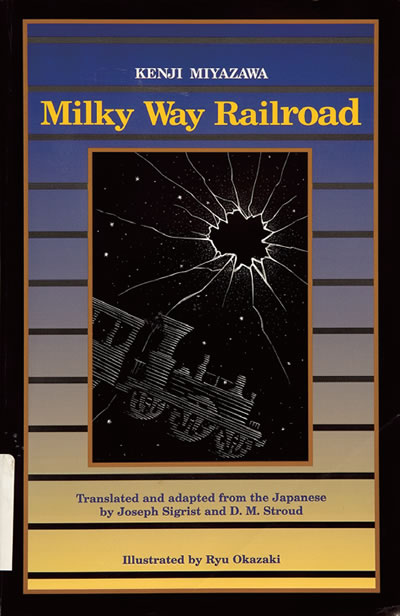

In the original of “Ginga tetsudo no yoru,” for example, the leading characters were two boys called Giovanni and Campanella. In the English edition “Milky way railroad” (No.283), their names were changed to the Japanese names Kenji and Minoru. In a preface to the translated version, the translator says that he changed the leading characters' names because the Italian names of the original might confuse the readers. Its Chinese edition (No.285) published by Hope Publishing Company depicts a tatami-mat room in Giovanni's house, where his mother clad in kimono lies on a futon (Japanese-style bedding), and a hanging scroll is suspended from the wall. When reading the scene depicting asparagus, kale, tomato and bread in his house, most Japanese illustrators for children's picture books would call up an image of a Western country or a scene of westernized life in Japan. Illustrations drawn by and picture books illustrated by Japanese artists depict Giovanni having a meal at a table and his mother sleeping in a bed. (No.281 and No.282)

There are some other changes made to the translated version. One of his works' greatest attractions is his use of onomatopoeia with a nice and interesting ring to it. When the original is translated into English or Chinese, languages that are not rich in onomatopoeia, words that imitate the sounds the onomatopoeia represent are often omitted or replaced by explanatory remarks.

For copyright reasons, images of some books are not available in this electronic exhibition.

- TOP

- Part 3 Special Corners

- Kenji Miyazawa: His works spread transcending national boundaries