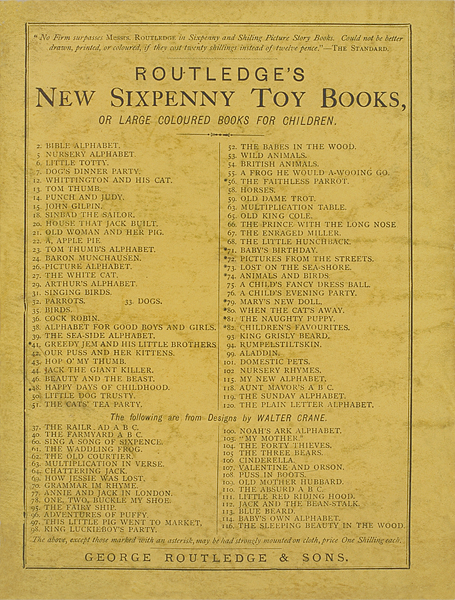

CONTENTS

Bibliography

Puss In Boots.

London: George Routledge & Sons,

1875 (1873).

8 pages.

248×188mm.

1/14

Introduction

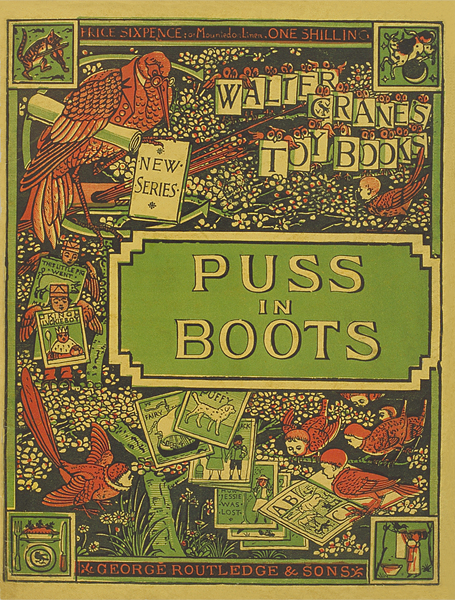

This is the classic story of the miller who died, leaving his mill to the eldest son, a mule to his second son, and the cat to his third son. Thanks to the exploits of the cat, however, the third son becomes the master of a castle and marries a princess. Published starting in 1873 as one of Walter Crane’s “Toy Books,” it was republished by John Lane for the Christmas market in 1895. It is said that the image of the third son that appears on the inside cover of the new edition was a self-portrait of the young Crane himself.

2/14

Puss In Boots

4/14 Push an image to enlarge

(♪) A miller lay dying, --- he made his last will; he left his three sons his cat, ass, and mill: to the eldest the mill, to the second the ass; the third had the cat, and he cried out, “Alas! I must starve now, unless I take pussy to eat!”

(♪) “No, master,” said puss, “give me boots to my feet--- a pair of top-boots---and please leave me alive, and you shall just see how we’ll flourish and thrive.”

(♪) “No, master,” said puss, “give me boots to my feet--- a pair of top-boots---and please leave me alive, and you shall just see how we’ll flourish and thrive.”

Puss In Boots

5/14 Push an image to enlarge

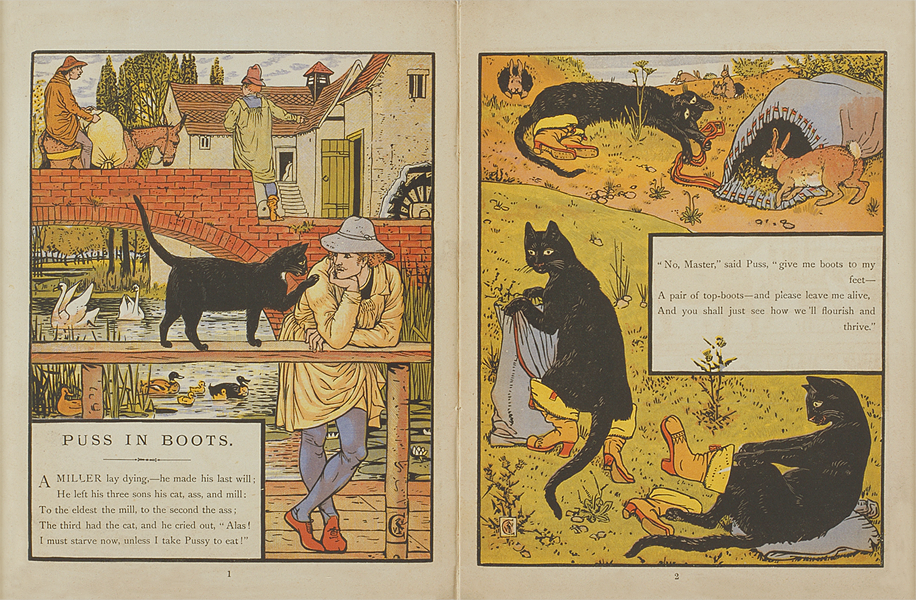

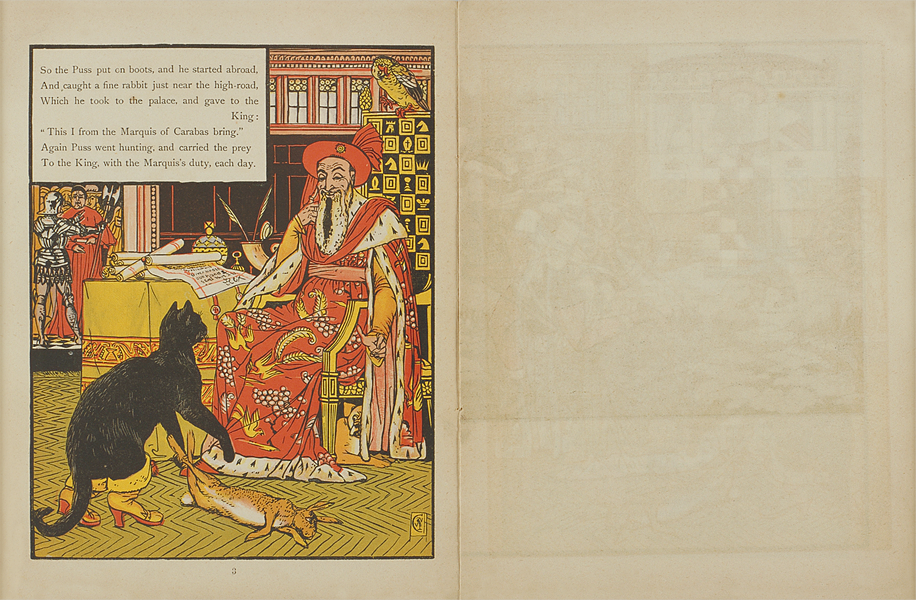

(♪) So the puss put on boots, and he started abroad, and caught a fine rabbit just near the high-road, which he took to the palace, and gave to the King: “This I from the Marquis of Carabas bring.” Again puss went hunting, and carried the prey to the King, with the Marquis’s duty, each day.

Puss In Boots

6/14 Push an image to enlarge

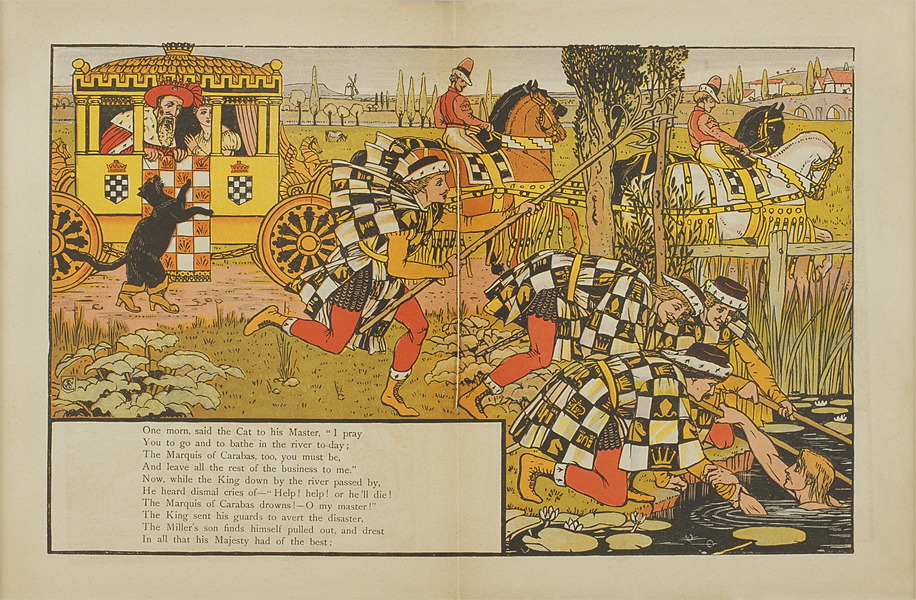

(♪) One morn, said the cat to his master, “I pray you to go and to bathe in the river to-day; the Marquis of Carabas, too, you must be, and leave all the rest of the business to me.” Now, while the King down by the river passed by, he heard dismal cries of---“Help! help! or he’ll die! The Marquis of Carabas drowns! ---O my master!” The King sent his guards to avert the disaster. The miller’s son finds himself pulled out, and drest in all that His Majesty had of the best;

Puss In Boots

7/14 Push an image to enlarge

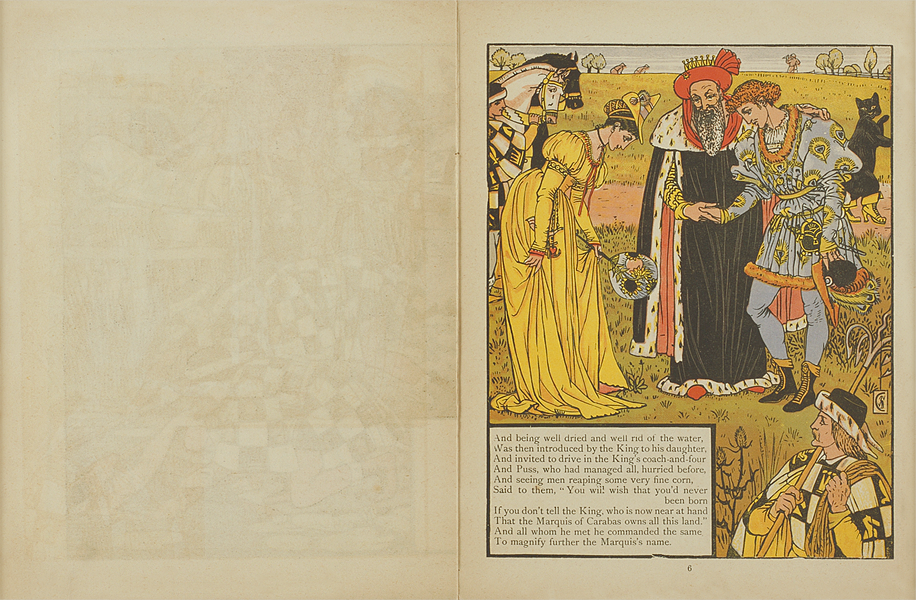

(♪) And being well dried and well rid of the water, was then introduced by the King to his daughter, and invited to drive in the King’s coach-and-four; and puss, who had managed all, hurried before, and seeing men reaping some very fine corn, said to them, “You will wish that you’d never been born, If you don’t tell the King, who is now near at hand that the Marquis of Carabas owns all this land.” And all whom he met he commanded the same, to magnify further the Marquis’s name.

Puss In Boots

8/14 Push an image to enlarge

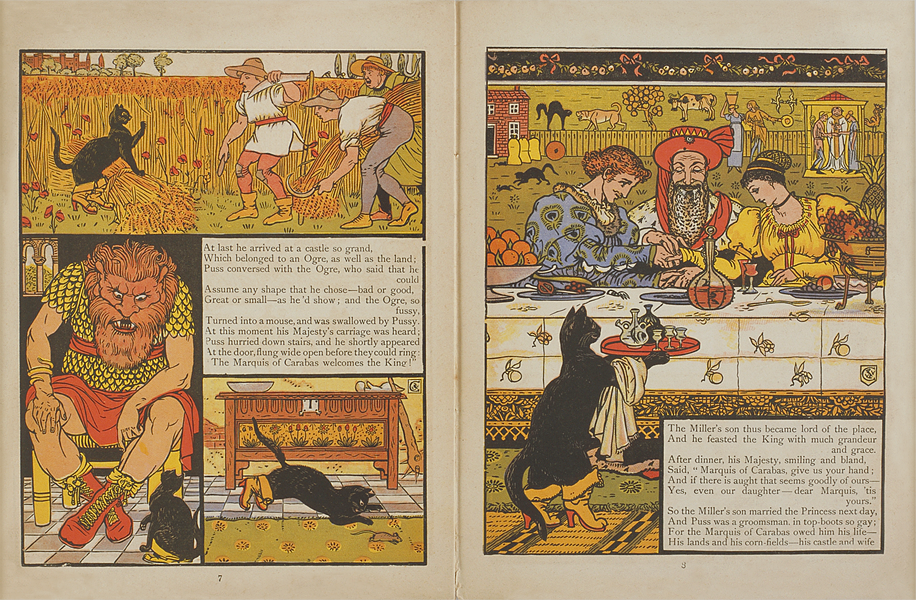

Left-side:

(♪) At last he arrived at a castle so grand, which belonged to an ogre, as well as the land; puss conversed with the ogre, who said that he could assume any shape that he chose---bad or good, great or small---as he’d show; and the ogre, so fussy, turned into a mouse, and was swallowed by pussy. At this moment His Majesty’s carriage was heard; puss hurried down stairs, and he shortly appeared at the door, flung wide open before they could ring: The Marquis of Carabas welcomes the King!”Right-side:

(♪) The miller’s son thus became lord of the place, and he feasted the King with much grandeur and grace. After dinner, His Majesty, smiling and bland, said, “Marquis of Carabas, give us your hand; and if there is aught that seems goodly of ours--- yes, even our daughter---dear Marquis, ‘tis yours.” So the miller’s son married the princess next day, and puss was a groomsman, in top-boots so gay; for the Marquis of Carabas owed him his life--- his lands and his corn-fields---his castle and wife.

No narration on page 9

Puss In Boots

9/14 Push an image to enlarge

No narration on page 10

About the author 1/4

Walter Crane (1845-1915)\

1)

Born in Liverpool, England, the son of portrait painter Thomas Crane, Walter demonstrated remarkable talent in painting from a young age. Having been raised in an environment that strongly nurtured his talent, he was apprenticed at the age of thirteen to the eminent London wood engraver W. J. Linton. Engravers were dubbed “woodpeckers” in those days. In the daytime they worked lined up in a row in front of a window, and at night they huddled in circles at round tables with a gas lamp set in the middle. In the daytime crane dedicated himself to learning technique, and in the evening he and the Linton’s son would go off to play hide and seek in the neighborhood chapel, or go watch the boats on the nearby river. Sometimes Walter would get young Linton to show him books. For three years he spent much time at the local zoo sketching animals, which became the basis for his later paintings.

10/14

No narration on page 11

About the author 2/4

2)

When he was sixteen, he worked as a press artist---whose function was that of today’s photo journalist---but the emphasis on fidelity and accuracy and the need to suppress imagination and creativity were not satisfying. Crane became independent at seventeen. Gradually as form and style took precedence in his work over recreating reality for magazine illustrations, he grew into an artist with strong powers of definition and the ability to use lines to express light and shadow. Increasingly, he was drawn to imaginary themes, as well as children’s book illustrations, which are subject to fewer constraints imposed by the text.

11/14

No narration on page 12

About the author 3/4

3)

In 1863 he met Edmund Evans, a young engraver who was searching for ways to do color printing. Together they broke away from the simple notion that held sway among the printers of the day that ”bright colors are best for children.” He also broke new ground in his children’s books with animals as the main characters, and in the skillful way he combined the precision of the natural scientist with humor and affection. During the time of transition in the Victorian age he sought to create the best designs for children with emphasis on the child’s point of view. He eventually became a leader in England’s golden age of picture books.

12/14

No narration on page 13

About the author 4/4

4)

Crane did a number of noteworthy painting that were heavily influenced by the Italian Renaissance of the fifteenth century, including “Love’s Sanctuary” (1870) and “The Renaissance of Venus” (1877). In 1882 he published wood engravings for “The Goose Girl,” which was published in Household Stories of the Brothers Grimm (1892), and those engravings became the basis for some of William Morris’s tapestries. Depicting a strange and illusory world that stretched beyond the borders of the illustration, the engravings became a prime example of art nouveau. Later, he joined the Arts and Crafts Movement in a quest to combine ornament and utility, or aesthetic and function. This conjunction of beauty and use was part of the essence of fin de siècle art, and Crane wrote a number of essays about the theory of the movement. A fervent socialist, he produced many works expressing his political beliefs, one of which was his May Day poster series that reflected the concerns of the English intelligentsia of the time. His influence spread well beyond England, partly through the cover illustrations he made for the German magazine Jugend.

13/14

Contents

14/14