本文

Bibliography

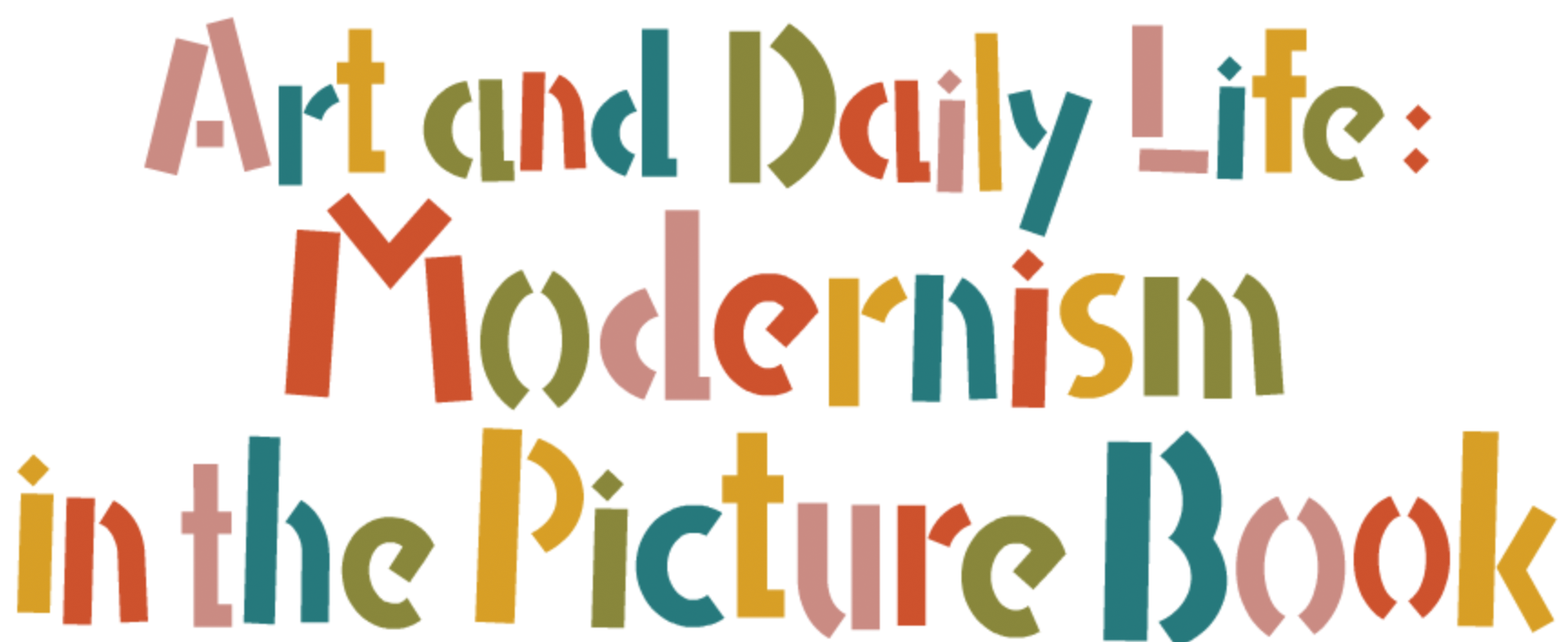

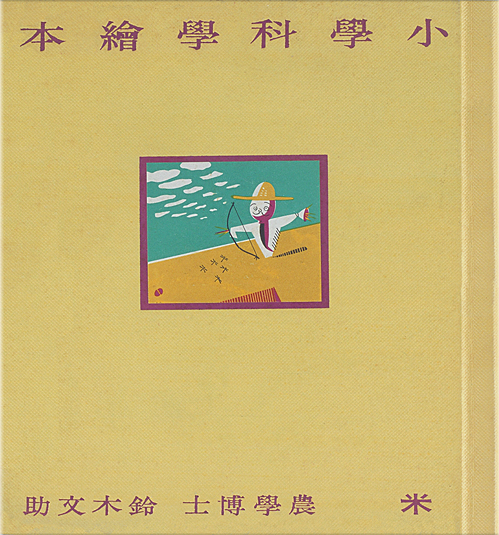

Rice: Elementary Science Picture Book Series, vol.11

Tokyosha; Tokyo.

1937,

32pages.

210x195 mm.

1/28

Rice

2/28 Push an image to enlarge

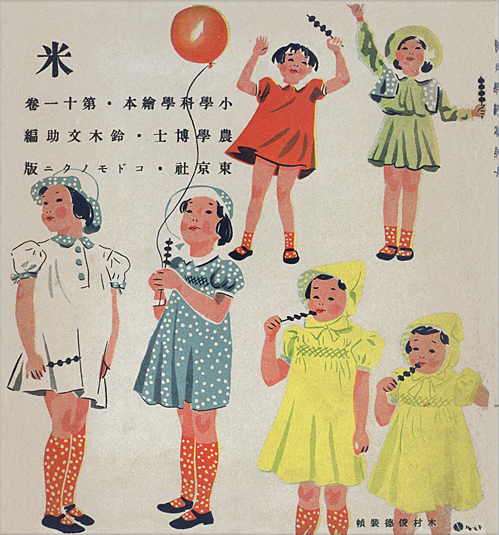

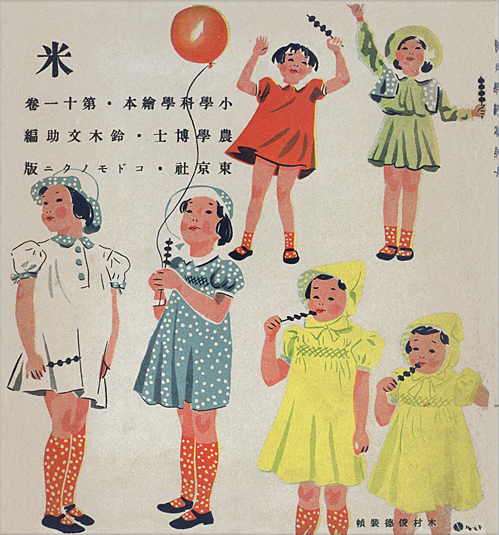

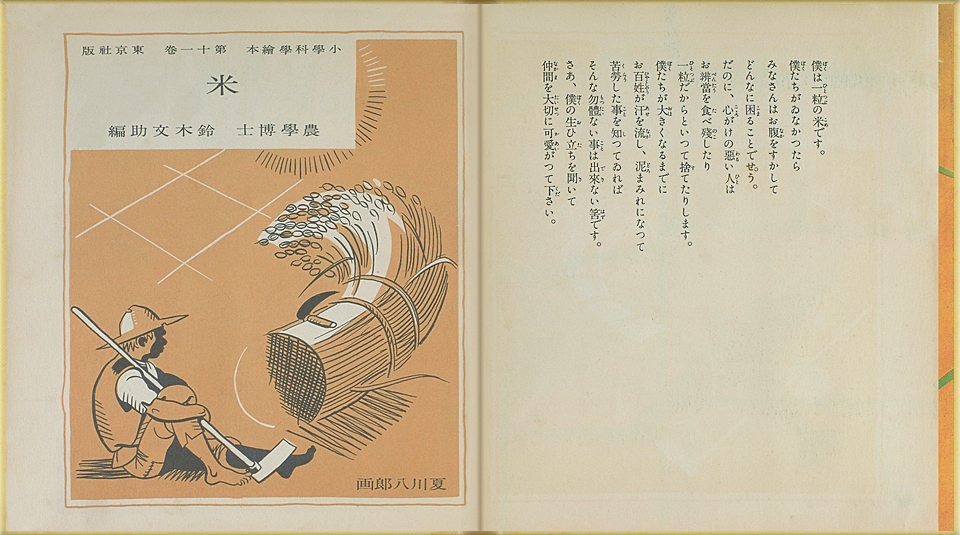

(♪) Rice: the eleventh volume of Elementary Science Picture Book Series. Compiled by Bunsuke Suzuki. Illustrated by Hachiro Natsukawa (Pseudonym of Masamu Yanase)

No narration on page 3

Rice

3/28 Push an image to enlarge

No narration on page 4

Rice

4/28 Push an image to enlarge

Rice

5/28 Push an image to enlarge

(♪) The Voice of a Grain of Rice. The book begins with the murmurings of a grain of rice, wishing that people would savor and appreciate every kernel. The story tells the long history of human reliance on rice, the toil of cultivation, its value as the staple of the diet, the battle against pests, and the variety of uses of rice and its byproducts. The book was published in 1937, and the text reflects its times with its old-style characters and phonetic syllabary as well as its references in some passages to Korea and Taiwan as Japanese territories. We will have opportunity to touch on this background again below.

Rice

6/28 Push an image to enlarge

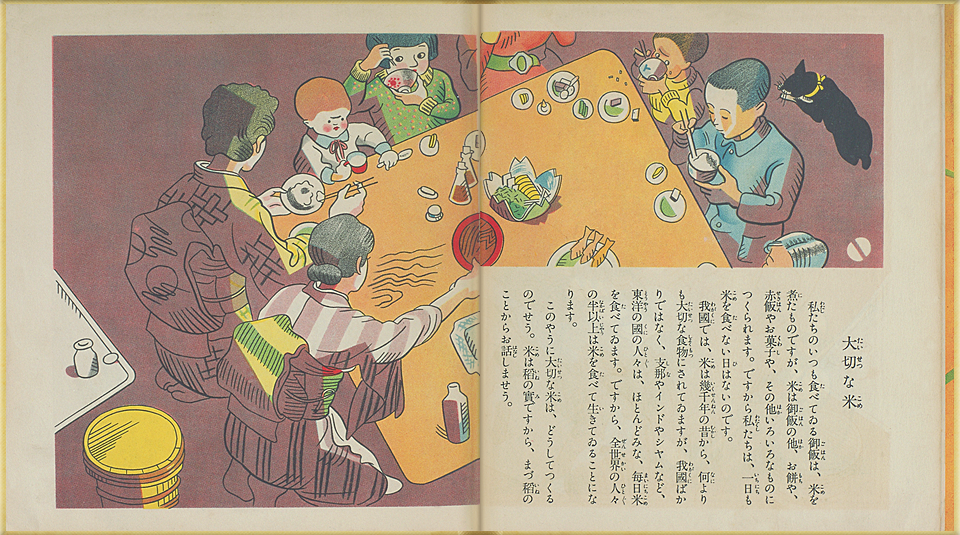

(♪) Valuable Rice. The picture shows a typical family meal of 1930s Japan. The children are eating bowls full of rice. Rice was the staple food not only in Japan but the mainstay of the diet throughout Asia. More than half the population of the world depends on rice for food. So how is this precious food grown? Here begins the story of the history and cultivation of rice.

Rice

7/28 Push an image to enlarge

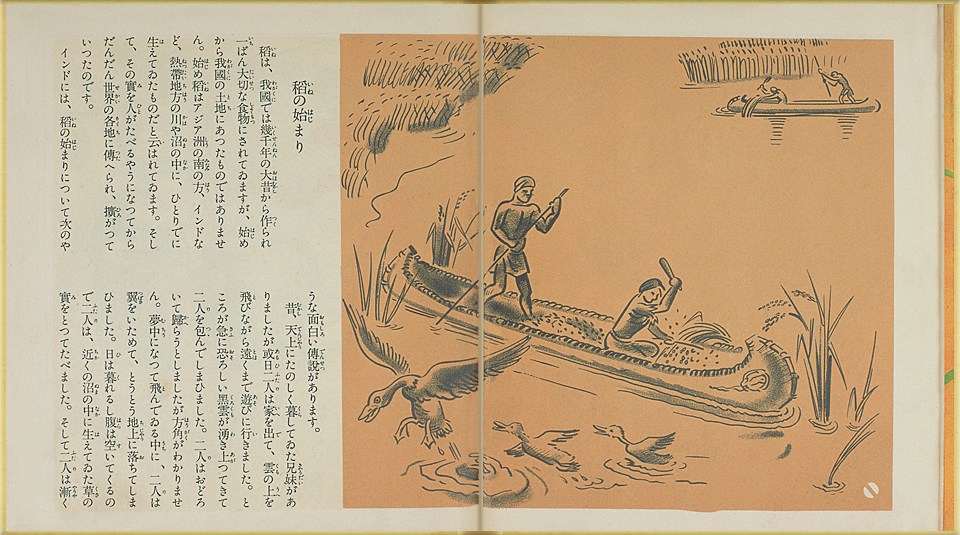

(♪) The Beginnings of Cultivated Rice. The history of rice is introduced on this and the following pages. The origin of rice is said to have been the tropical regions of southern Asia, such as India. At first it was wild, growing along rivers and in wetland areas. The picture shows how people cut rice growing in the marshes, and then threshed it with a mallet to remove the grains.

Rice

8/28 Push an image to enlarge

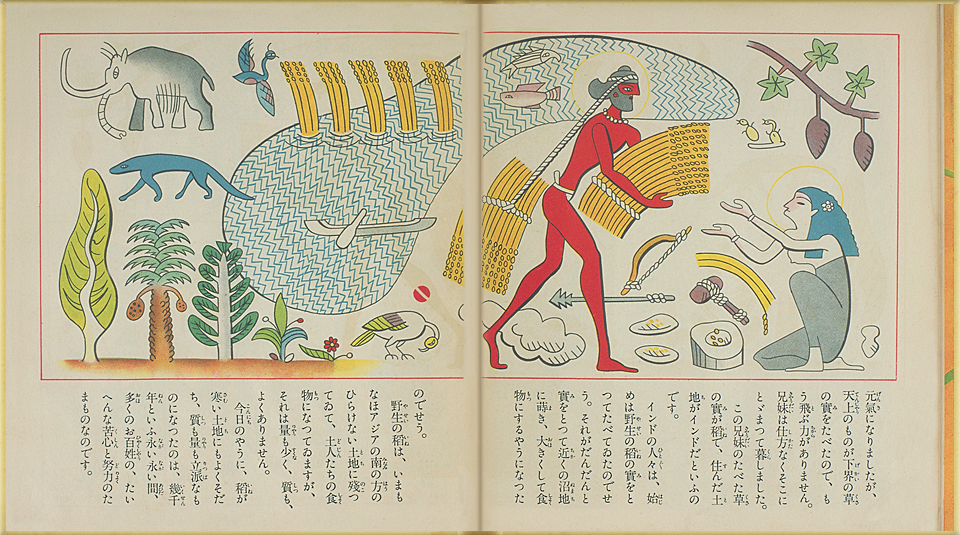

(♪) Legends about Rice. In India, the legend of the beginning of rice cultivation goes as follows. Long, long ago there was a brother and sister who lived happily in heaven. One day, when they went out for a pleasure trip, they were suddenly caught up in a black cloud. Their wings damaged, they fell down and landed on Earth. When they got hungry, they ate the grain of grasses growing in the marshes. But inhabitants of heaven who partook of food on Earth lost their powers of flight forever, so the brother and sister could not return to Heaven. The place they remained was India and the grains they ate were rice, so goes the story. The scene on these pages shows people using a mortar and mallet to remove the grain from the sheaves of rice.

Rice

9/28 Push an image to enlarge

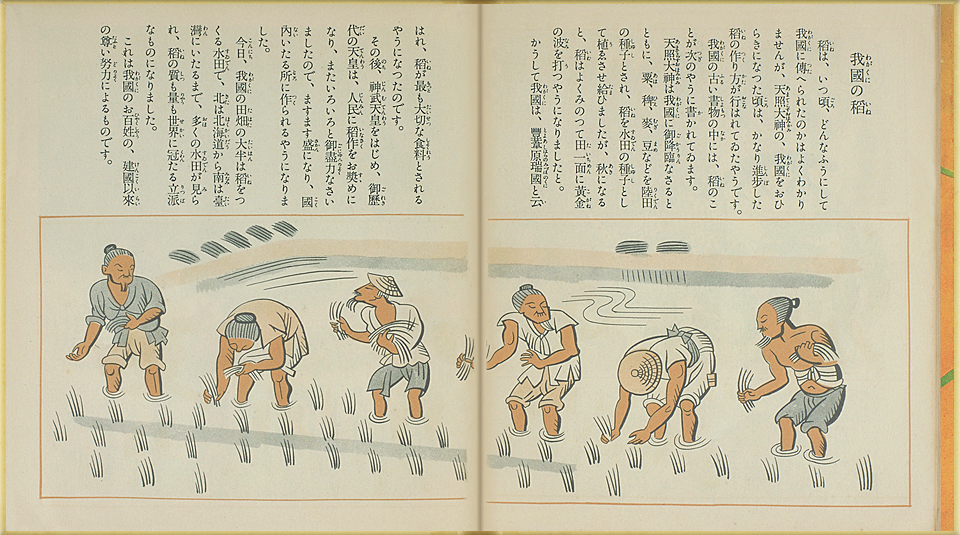

(♪) Rice in Our Country. The history of rice is here presented using the Japanese myth that tells how the goddess Amaterasu-omikami descended to earth and propagated rice, along with millet and barley. In fact, rice cultivation, introduced both from the continent and the islands of the South Pacific from the late Jomon to the Yayoi periods, some two thousand years ago or before, appears to have been practiced quite extensively. Ancient Japanese called their country “the land where abundant rice shoots ripen beautifully,” a name that suggests the importance accorded to rice since long ago.

Rice

10/28 Push an image to enlarge

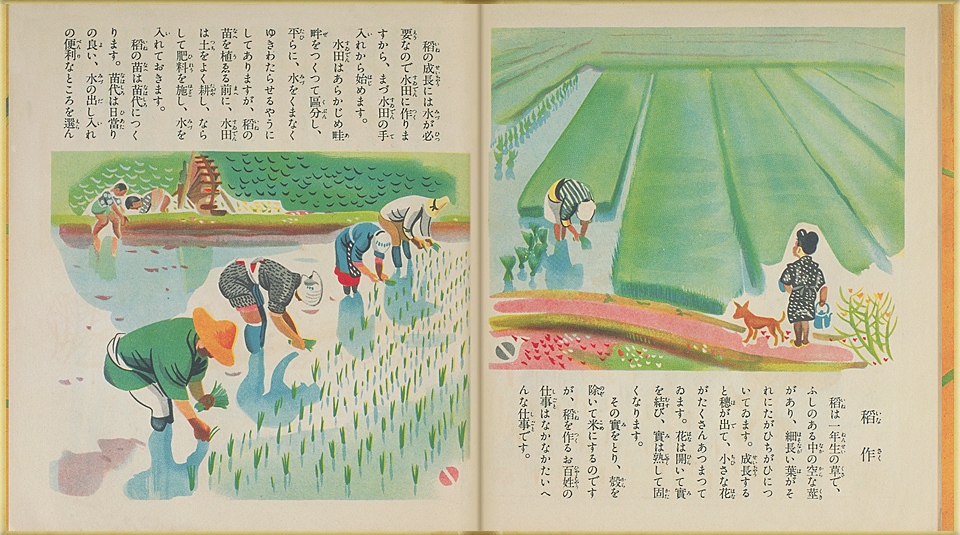

(♪) Wet-Rice Cultivation. The three spreads of pages beginning here describe the process of wet-rice cultivation from building rice paddies to the harvest of rice. We no longer see the traditional costume of farmers or the old-style farming implements in use any more, but the tasks of growing rice extending throughout the year have in fact changed little from long ago. The right-hand page shows rice planted densely in a seedling bed. A little girl is bringing tea to her mother, who is bundling up the seedlings for planting. At busy times of the rice-growing season, even children were expected to help. At the top of the left page the farmers are building up the ridges and filling the paddies with water. Below, people are already hard at work, planting the rice seedlings.

Rice

11/28 Push an image to enlarge

(♪) The Tasks of Wet-Rice Farming. The description of the jobs involved with rice farming continues here. The soil is cultivated and fertilizer added and then water is let into the paddy. Seed rice is sown in seedling beds and grown to a height of several centimeters before transplanting to the paddies. The transplanting usually takes place during the rainy season. Much hard work is done throughout the summer, such as making sure the paddy has a steady supply of water and pulling weeds in the blazing sun, to nurture the rice. If all goes well, this labor is rewarded and the rice grows, and by the end of summer its heads ripen.

Rice

12/28 Push an image to enlarge

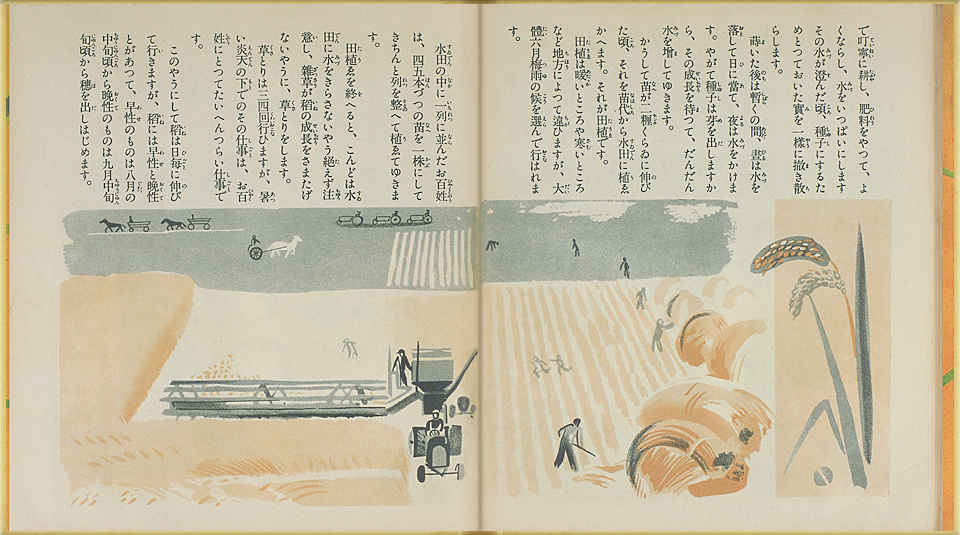

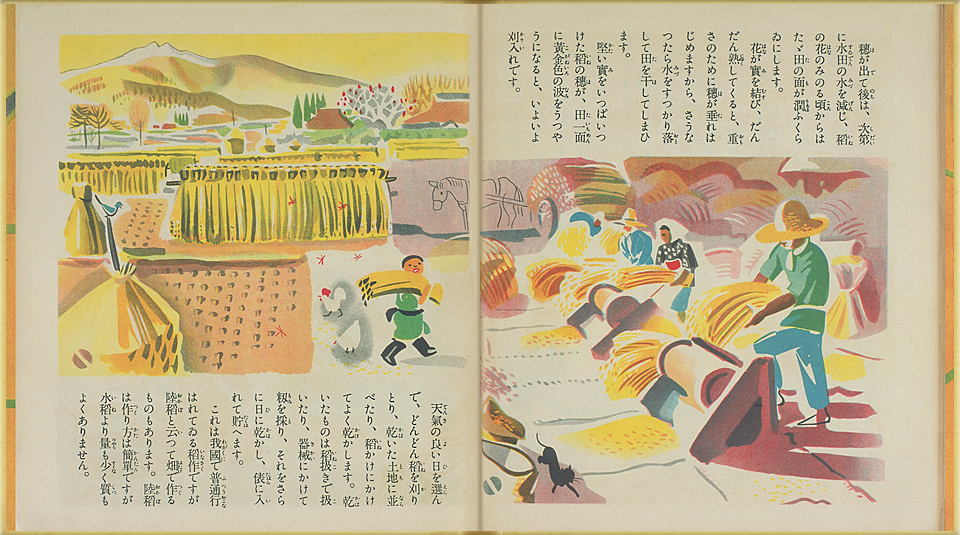

(♪) Autumn’s Harvest. The rice puts forth ears that flower and then form the grain. As the grain ripens, the ears begin to droop from the weight. The water in the paddies is decreased and then drained out. Now comes the harvest of autumn. The farmer’s work continues. After cutting the rice, it must be left to dry. Then it is hulled and placed in bales. The left-hand page shows how sheaves of rice are hung up to dry. The right page illustrates how a threshing device is used to remove the grain from the stalks. In addition to growing in paddies, it explains, rice can also be cultivated in dry fields.

Rice

13/28 Push an image to enlarge

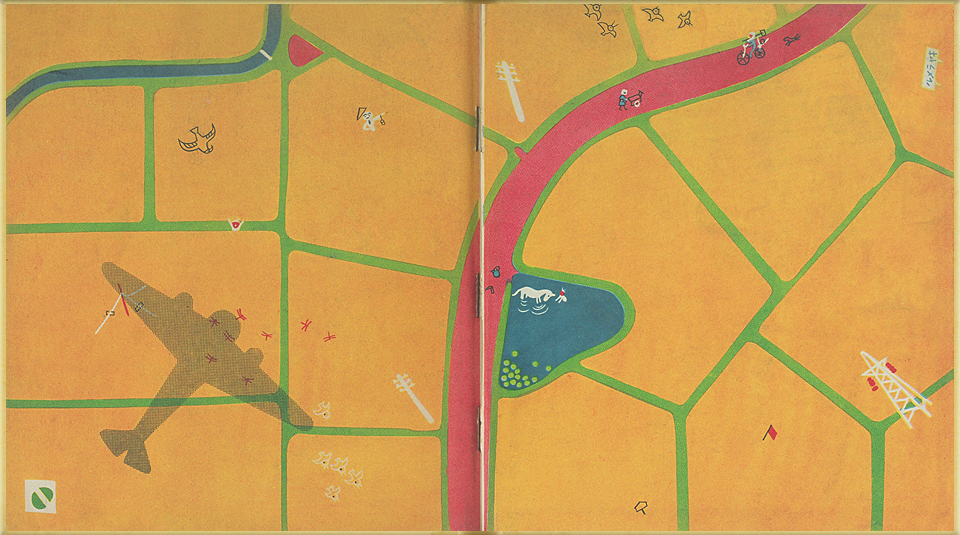

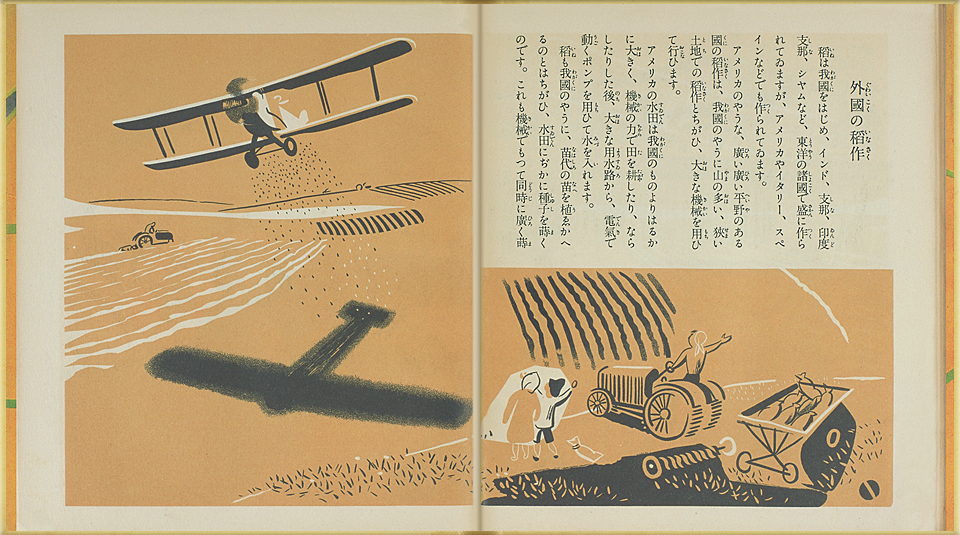

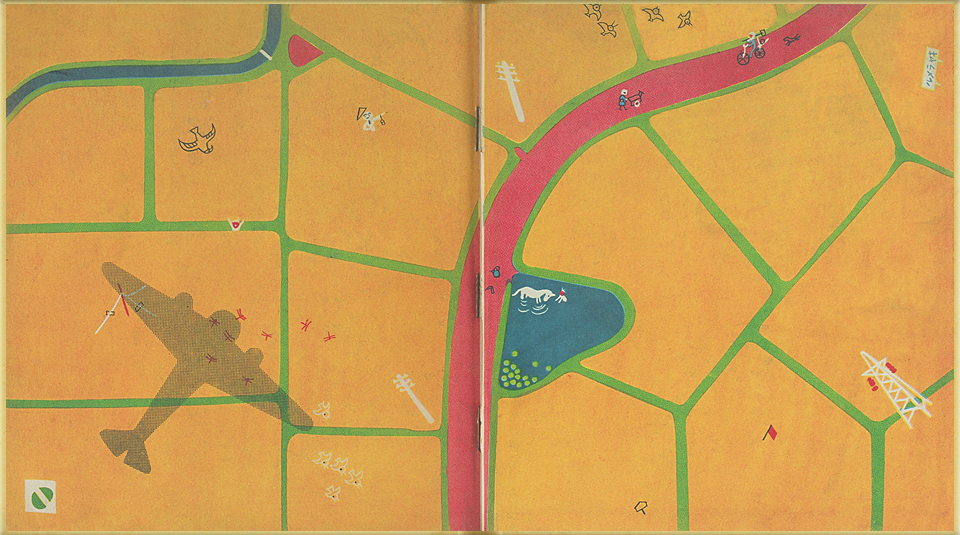

(♪) Rice Cultivation in Other Countries. The next two spreads of pages show how rice is cultivated in other countries. It shows how widely machines are used, especially in the United States, from plowing of the fields by tractor to irrigation water control by electric-powered pump, and even sowing of seed by airplane. The picture evokes an image of how free and easy it must be to wing over such broad fields, scattering the seeds from on high.

Rice

14/28 Push an image to enlarge

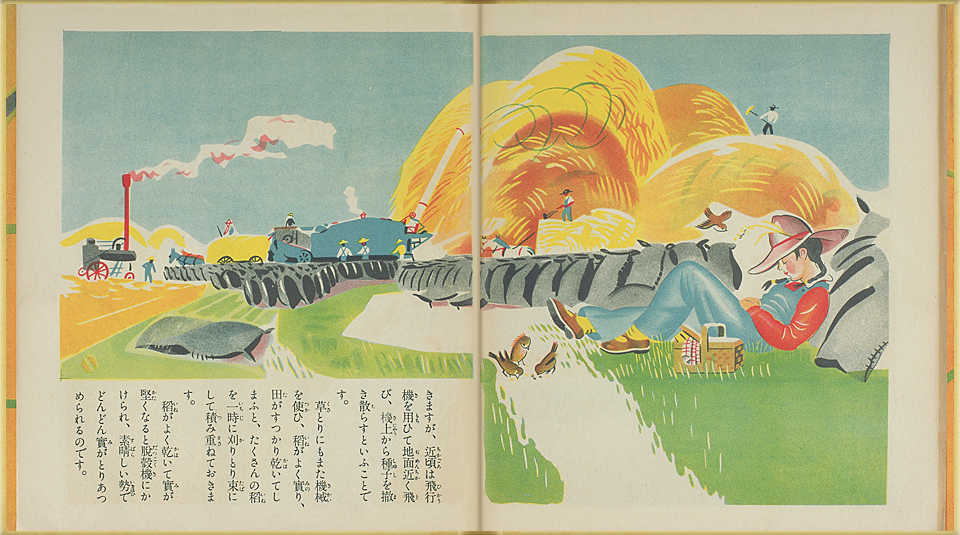

(♪) Everything Done by Machine. Where even the sowing of seeds is done by airplane, there is none of the bundling of seedlings and transplanting to paddies. How different it is from the method in Japan where the farmers work together in the fields, bending over and over to transplant the seedlings. The weeding required in summer, the reaping, the hulling—everything is done using the power of machines. That being the case, a boy might even be forgiven for taking a nap with a bag of rice as a pillow.

Rice

15/28 Push an image to enlarge

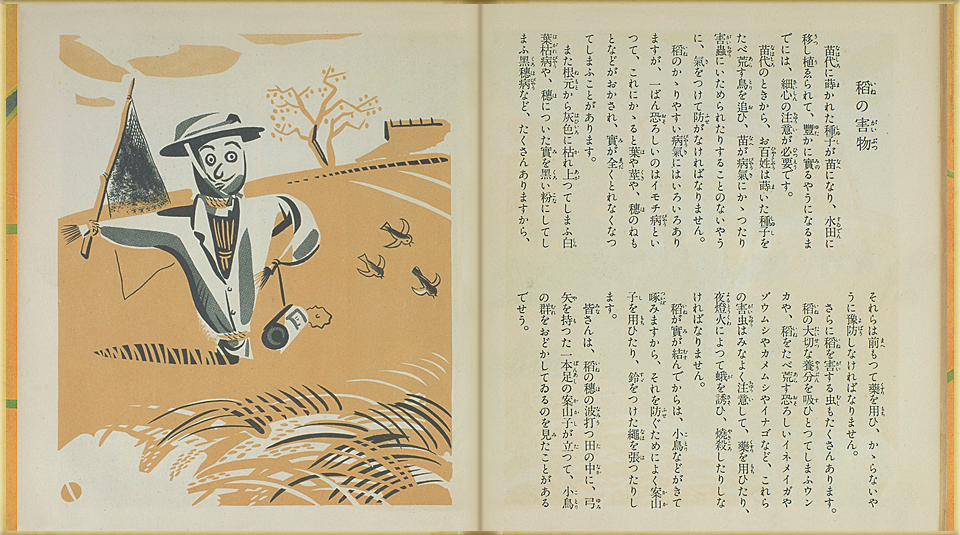

(♪) Threats to Rice Crops. This page explains the diseases and pests that threaten rice crops. As the most common diseases are rice blast, leaf blight, and smut. Insect pests include the leafhoppers that suck nutrients from the rice stalks, and the grasshoppers and rice stem borer moths that eat the leaves. In the autumn around harvest time, birds vie with humans for the bounty. In the days before the use of agricultural chemicals, the farmer had to protect the crop from many kinds of harm. The scarecrow on the left-hand page—has a distinctly foreign air.

Rice

16/28 Push an image to enlarge

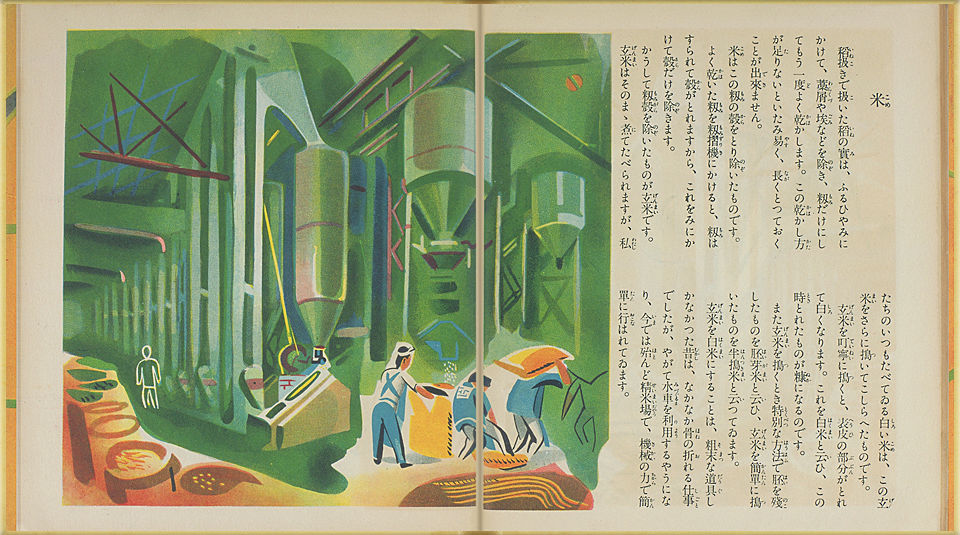

(♪) Rice. This section explains how the grain grown in the fields is processed. The unhulled rice collected in the granaries is put through a machine to remove the husks. This yields brown or unpolished rice. White rice, the rice we are most accustomed to eating, is produced by removing the bran from the kernels. The process of removing the bran was once performed using a waterwheel. Rice-polishing machines were just beginning to be used. The left page shows a rice-cleaning mill; we can almost hear the roaring of the machines.

Rice

17/28 Push an image to enlarge

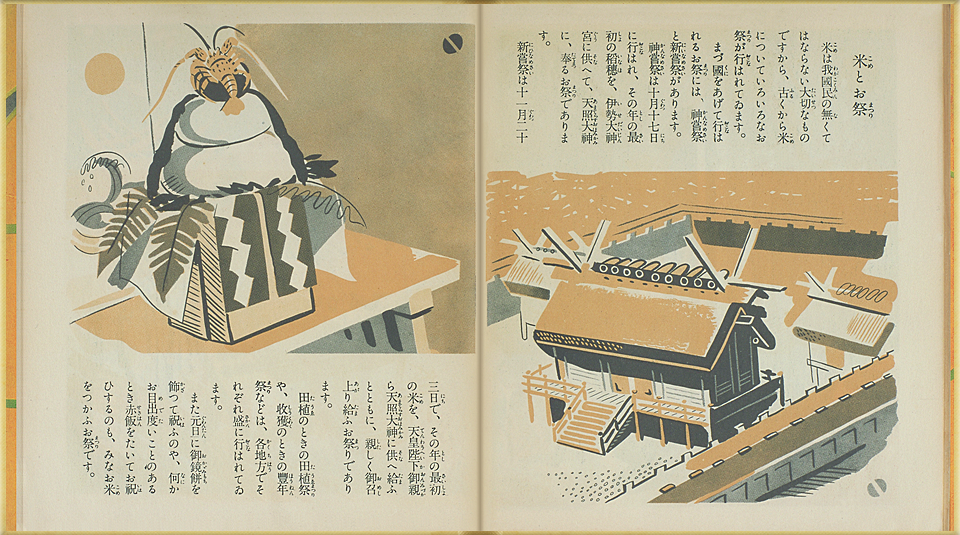

(♪) Rice and Ritual. After the harvest, various kinds of rites are held in thanks for a bountiful crop. The two leading harvest rites are called the Kannamesai and the Niinamesai. At the Kannamesai stalks of the first harvested rice are offered to the deities at Ise Shrine. The Niinamesai, held within the imperial palace by the emperor, is a rite at which the newly harvested rice is offered to the gods. Today’s national holiday Labor Thanksgiving Day coincides with the celebration of the Niinamesai in November. Harvest festivals are held all over the country. Mochi rice cakes made at New Years and sekihan (red rice) boiled with adzuki beans are special ways of preparing rice for auspicious occasions.

Rice

18/28 Push an image to enlarge

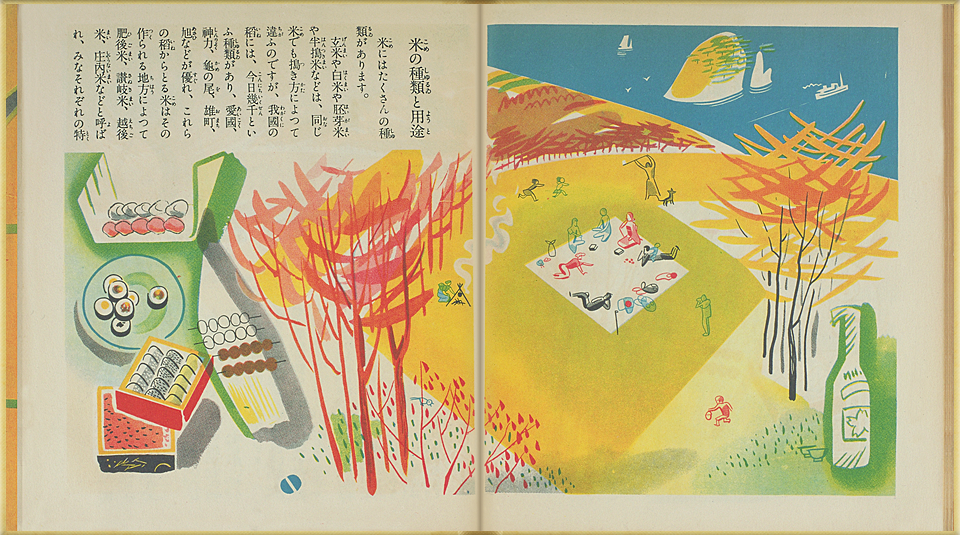

(♪) Types of Rice. This and the following spread of pages shows the types of rice and their uses. The names of the rice given in the text—“Aikoku” (Love of Country) and “Jinriki” (Power of the Gods)—mirror the times. The names of varieties of rice, then associated with different parts of the country (Higo, Sanuki, Echigo, etc.), correspond to names like the Koshihikari and Sasanishiki varieties most common today. As explained on this and the following pages, Japanese rice is divided into two main types: nonglutinous and glutinous rice. As explained in the text, the nonglutinous rice (uruchi-mai) is the type eaten everyday; the glutinous type (mochi-gome) is used for making mochi rice cakes and rice-based confections.

Rice

19/28 Push an image to enlarge

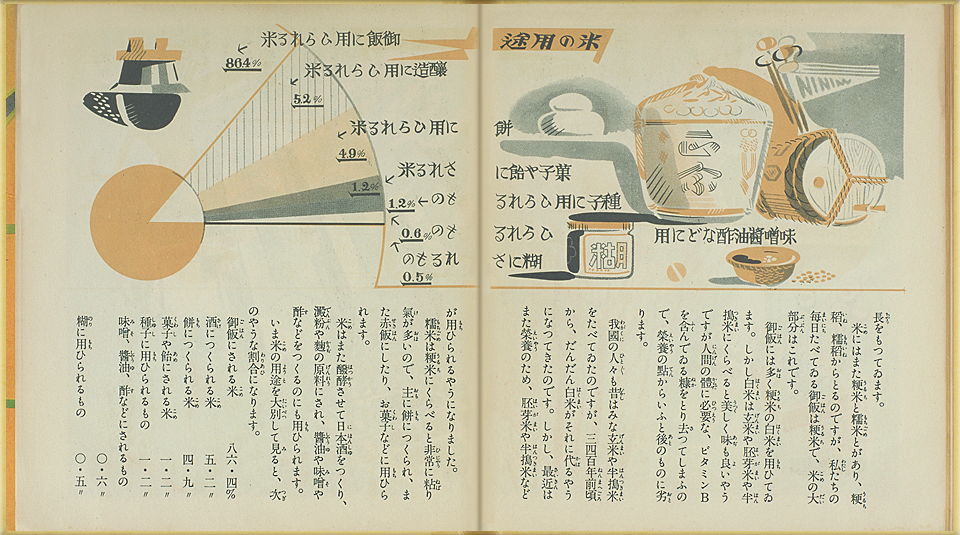

(♪) Uses of Rice. This section outlines the way rice is used. In addition to the ceremonial dishes like mochi and sekihan, and sweets, as described above, nonglutinous rice is processed to make sake, miso, shoyu, vinegar, and other products. The diagram indicates that 86.4 percent of rice is consumed as table rice at meals. It demonstrates the importance of rice in the Japanese diet. The labels for the diagrams and sketches are written from right to left, as was the custom for horizontal writing in those days.

Rice

20/28 Push an image to enlarge

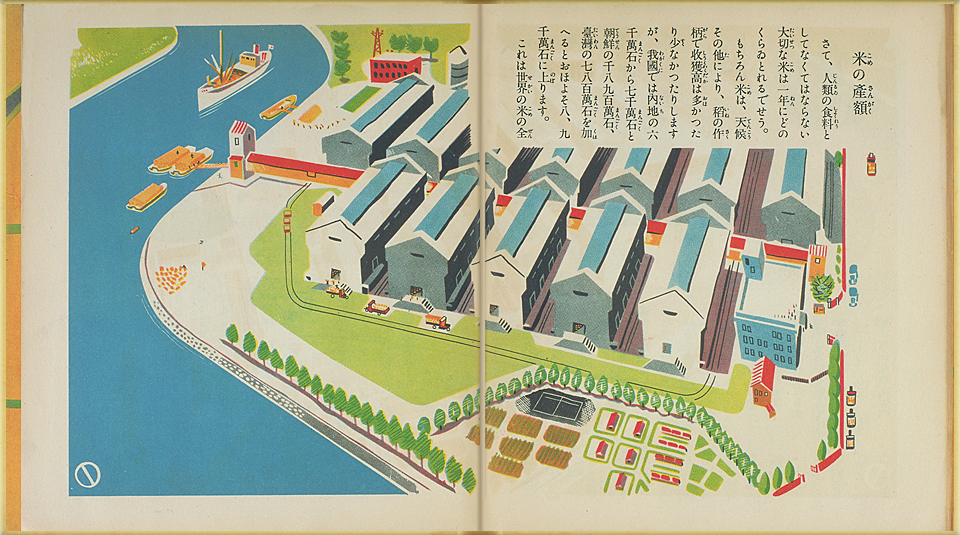

(♪) Amount of Rice Production. These pages give figures for the amount of rice produced in Japan and in the world in 1932. Reflecting the times when this book was made, the figures for Korea and Taiwan are included, along with those for Japan proper. The book says that 15 percent of the rice in the world is produced in Japan.

Rice

21/28 Push an image to enlarge

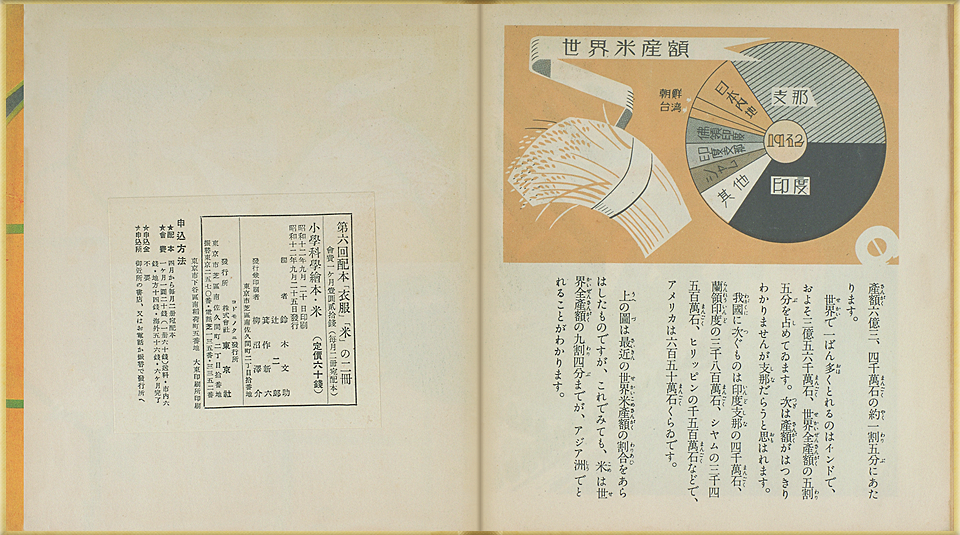

(♪) Diagram of Rice Production. The top producer of rice in the world is shown as India (55 percent), followed by China. Japan is placed third. In this graph, though, India and China are shown as producing roughly the same proportion. The accuracy of its details aside, the diagram shows that 94 percent of rice is produced in Asia. It illustrates how important rice is as a food to people, Japanese included, throughout Asia.

(♪) Colophon. This book was published in September 1937, the year after the February 26 attempted coup d’état by young military officers and the beginning of domination of the government by the military forces. In July 1937 the Marco Polo Bridge Incident had triggered the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War. It was at this ominous time that this first series of elementary science picture books was published. Books like this are evidence that no matter what the times, there are always people devoted to the work of passing on knowledge and culture to children.

(♪) Colophon. This book was published in September 1937, the year after the February 26 attempted coup d’état by young military officers and the beginning of domination of the government by the military forces. In July 1937 the Marco Polo Bridge Incident had triggered the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War. It was at this ominous time that this first series of elementary science picture books was published. Books like this are evidence that no matter what the times, there are always people devoted to the work of passing on knowledge and culture to children.

No narration on page 22

Rice

22/28 Push an image to enlarge

No narration on page 23

Rice

23/28 Push an image to enlarge

No narration on page 24

Rice

24/28 Push an image to enlarge

No narration on page 25

About the author 1/3

Compiled by SUZUKI Bunsuke (1888-1949)

Pictures by NATSUKAWA Hachiro (pseudonym of YANASE Masamu) (1900-1945)\

1)

Tokyosha’s twelve-volume Elementary Science Picture Books is said to be the first science picture book series published in Japan. The subject-matter falls roughly into three categories: subterranean resources such as coal and iron, compiled by Mitsukuri Shinsaku, a science specialist, food commodities like rice and sugar, by agriculture specialist Suzuki Bunsuke, and airplanes, trains, and other forms of transportation by Tsuji Jiro, an engineering specialist. The names of the illustrators include leading names in avant-garde art movement during this time like Murayama Tomoyoshi, and Natsukawa Hachiro (pseudonym of Yanase Masamu). This extraordinary nonfiction series helped children learn about topics that were a familiar and basic part of their daily lives from the scientific and cultural points of view.

25/28

No narration on page 26

About the author 2/3

2)

Compiler Suzuki Bunsuke received his doctoral degree in biochemistry at Tokyo Imperial University Agriculture and Dendrology College. An adopted son of Suzuki Umetaro, famous for the discovery of Vitamin B1, Suzuki Bunsuke taught at the Kyoto Imperial University and later at Tokyo Imperial University, where he served for a time as the dean of the agricultural college. Natsukawa Hachiro (Yanase Masamu) was a talented artist active in painting, design, caricature, and photography said to be in the vanguard of the avant-garde movement. This work shows his success in harmoniously blending traditional and Western forms of expression. He died in Shinjuku Station when it was hit in an air raid during the final year of the war.

26/28

No narration on page 27

About the author 3/3

3)

Critics from early on pointed to the influence of the Petersham books published in the United States on the Elementary Science Picture Book Series. Its year of publication, 1937, however, should be noted. With the February 26 attempted coup d’état by young military officers the previous year and the Marco Polo Bridge Incident the same year, Japan had already stepped into the mire of the Sino-Japanese War that would drag it into the Pacific War. Despite the political atmosphere in which it was published, and without adopting slogans calling for increasing food production, this picture book deals with rice, upon which Japanese depended as the staple of their diet, in a genuinely scientific and cultural approach under the supervision of an experienced scholar. This is important when we consider the significance of these books for children.

27/28

Contents

28/28