本文

Bibliography

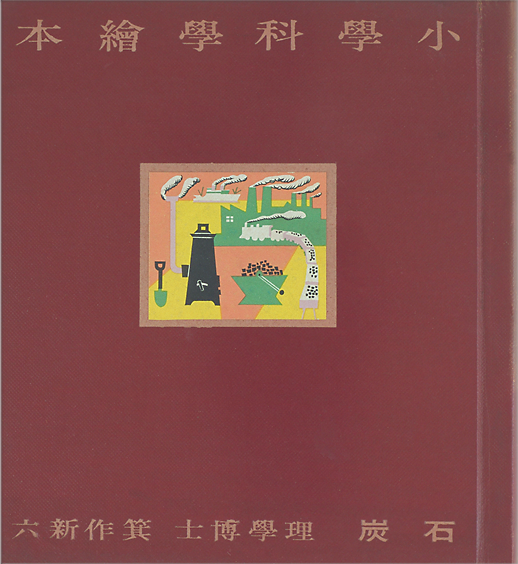

Coal: Elementary Science Picture Book Series, vol.9

Tokyosha; Tokyo.

1937,

32pages.

212x195 mm.

1/25

Coal

2/25 Push an image to enlarge

Coal: the ninth volume of Elementary Science Picture Book Series. Compiled by Shinroku Mitsukuri. Illustrated by Kenichi Yamashita.

No narration on page 3

Coal

3/25 Push an image to enlarge

Coal

4/25 Push an image to enlarge

Japan’s Two Leading Coal-Producing Areas. The story opens with two chunks of coal talking together. They speak in different dialects, one is from Kyushu, the other from Hokkaido, the two leading regions where coal is produced in Japan. The text is written in old-style characters and phonetic syllabary, as this picture book was published in 1937.

Coal

5/25 Push an image to enlarge

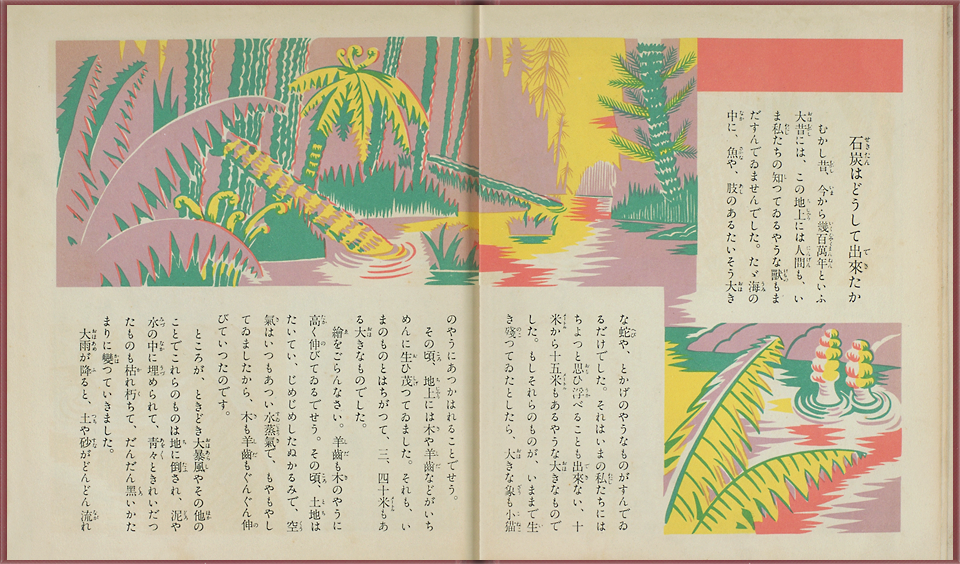

(♪) How Was Coal Created? This and the following spread of pages explain how coal came into being. Here is the landscape of the earth long ago, where swamps were surrounded by huge ferns and trees dozens of meters high. In the course of earthquakes, storms, and volcanic eruptions, vegetation was buried deep in the earth. Over the eons, under the pressure of the heat and weight of the earth, organic matter was carbonized and transformed into coal.

Coal

6/25 Push an image to enlarge

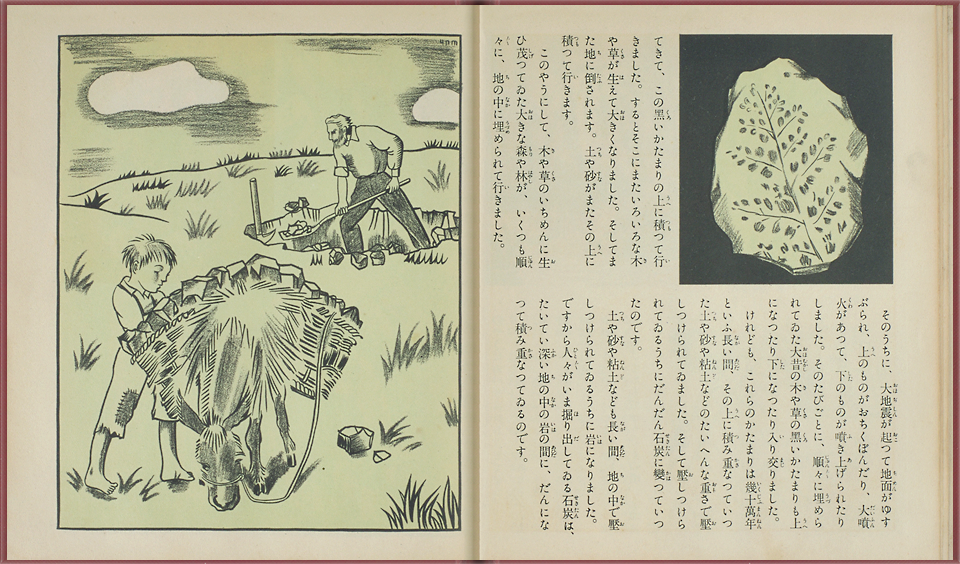

(♪) On the right-hand page is a sketch of a coal fossil. The imprint of fern leaves and bones of animals shows how coal was formed by the process described above. The picture on the left page depicts the collection of surface coal. Japan had few places where coal was found on the earth’s surface, but in other countries, veins of coal rising up close to the ground’s surface were often found. A man is digging coal with pick and shovel. A boy, perhaps helping his father, is packing the coal onto the back of a donkey.

Coal

7/25 Push an image to enlarge

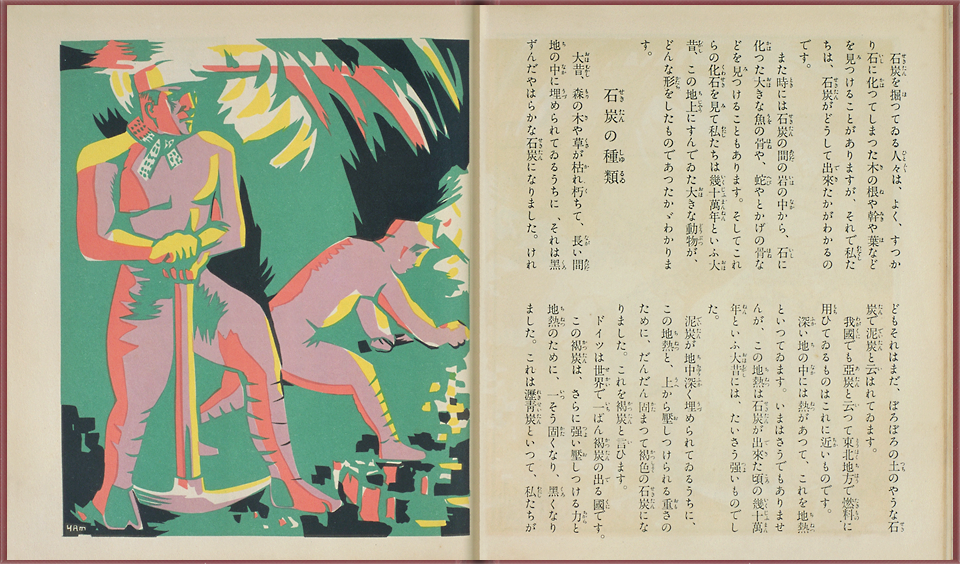

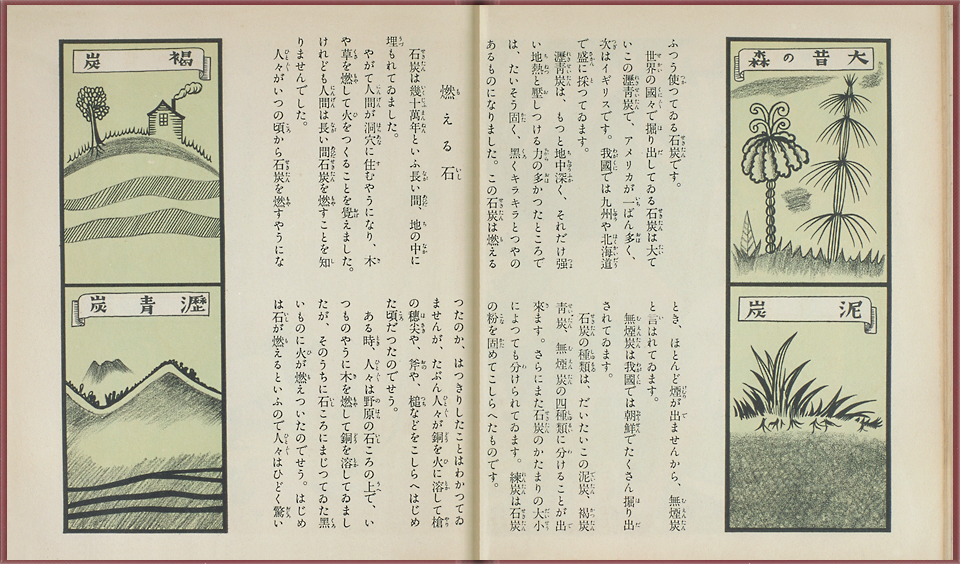

(♪) Types of Coal. On this page begins an explanation of the different types of coal. The substance formed when trees and ferns were buried in the earth and the mud became carbonized is called “peat.” This material makes very poor fuel. When this peat was buried deep in the earth and hardened by heat and pressure, it became lignite, also called brown or wood coal. The text explains that the largest producer of this type of coal is Germany.

Coal

8/25 Push an image to enlarge

(♪) The illustrations on the right and left sides show the different types of coal and the layers where they are found in the earth. Unlike today, when characters are written left to right, in the days this book was made, horizontal print was set running right to left. When brown coal was further heated and pressed within the earth, it changed to bituminous coal. What we usually call “coal’ is this hard, black bituminous type. Found in layers even deeper than bituminous coal and producing little smoke when burned is an even harder, blacker type of coal, called anthracite or stone coal. Peat, brown, bituminous, and anthracite are the four main types of coal. This picture book was published before 1945, during the period when Korea was a Japanese colony, as is revealed in the sentence saying that Korea is part of Japan.

Coal

9/25 Push an image to enlarge

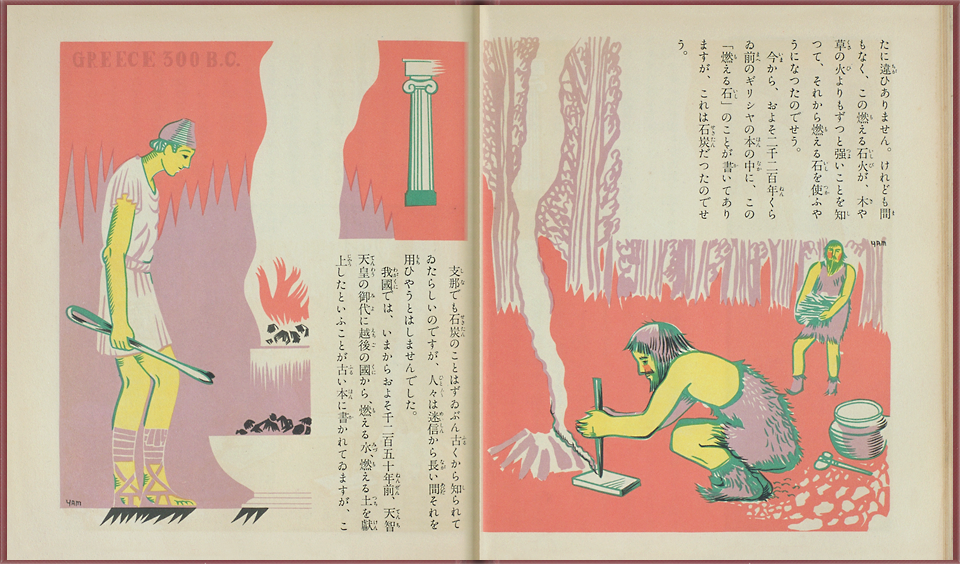

(♪) The Rocks that Burn. The story begins on the previous page with an episode about how the properties of coal were discovered. A long time ago, coal appears to have been discovered by people building campfires in the hills when they saw how the fire spread to some of the rocks sticking out of the earth. They called them “burning rocks.” The oldest source about coal is a book from ancient Greece about stones that describes it as a “black stone.” The picture on the left shows a Greek blacksmith at work at a coal-burning furnace.

Coal

10/25 Push an image to enlarge

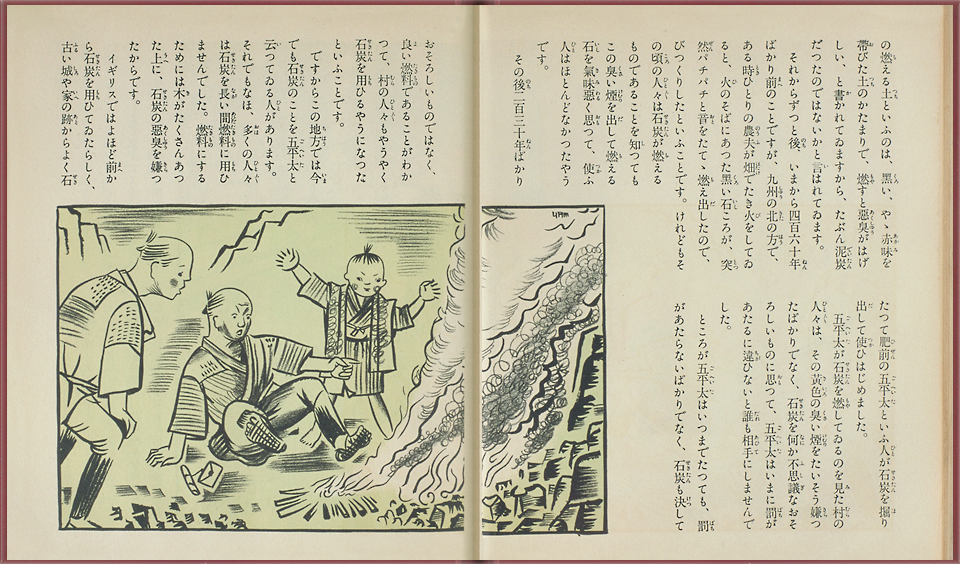

(♪) The History of Coal in Japan. What about Japan? One account from the time of the Emperor Tenchi in the seventh century tells how “burning rocks” and “burning water” were presented to the emperor as gifts from the province of Echigo. These must have been coal and petroleum. Much later in history came the scene illustrated on these pages. A farmer of northern Kyushu unwittingly discovered the “burning rocks” while sitting at his campfire. This is just like the story in other parts of the world. But apparently the smell of the burning coal was so unpleasant that it was not taken up for use as fuel at that time. In Japan, coal did not come into practical use until the Edo period (1603-1867). A man named Goheita of Hizen (present-day Nagasaki prefecture) was the first to start using coal as fuel. In that part of the country, therefore, coal was known for some time as “Goheita.”

Coal

11/25 Push an image to enlarge

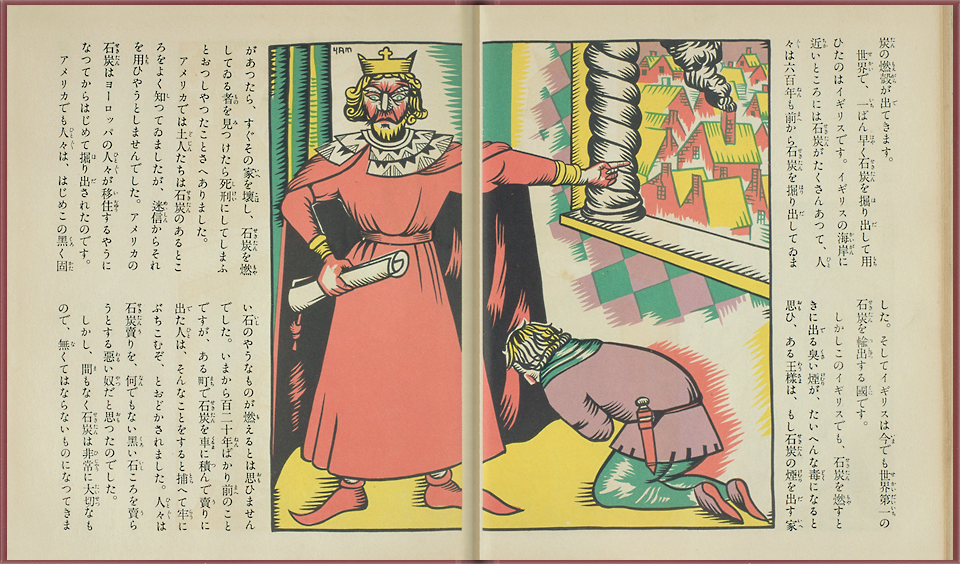

(♪) The History of Coal in Other Countries. The first country in the world to use coal as fuel was England, which had many excellent coal mines. At first, however, because of the bad smell and noxious gasses produced when coal is burned, in England its use was prohibited under the “Coal Prohibition Law.” Apparently those found burning coal would have their houses destroyed or even be sentenced to death. This would have been around the thirteenth or fourteenth century, during the time of King Edward I, as pictured in the illustration.

Coal

12/25 Push an image to enlarge

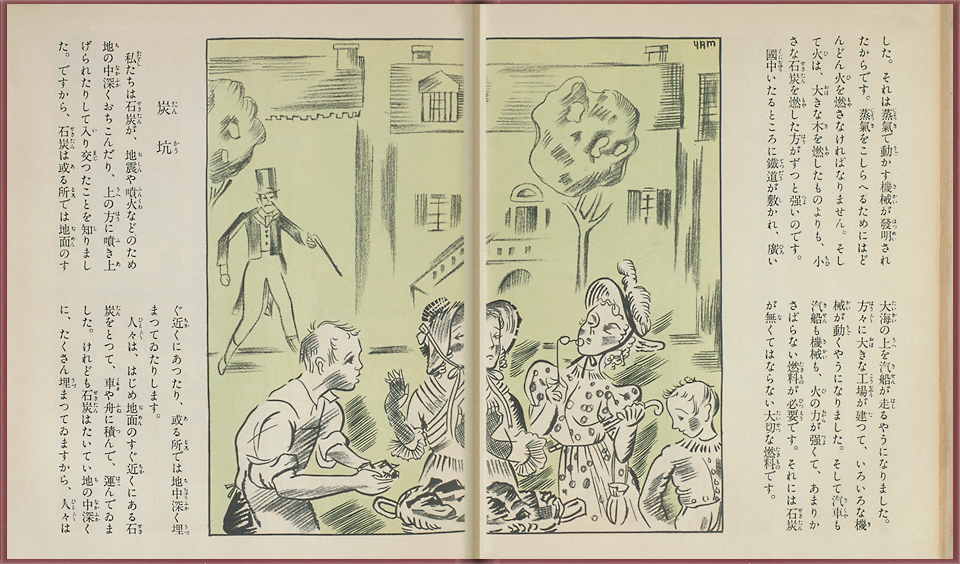

(♪) The use of coal in the United States spread after the number of immigrants from Europe had greatly increased. At first the “black stones” were not considered something that could be used as fuel, and are said to have been cases when coal peddlers were arrested and thrown into jail. The illustration shows a peddler hesitantly offering his wares to some fine ladies. As the industrial revolution gathered momentum, however, demand quite sharply arose for coal in massive quantity. With the invention of the steam engine, coal became the main source of fuel for railways, steamships, and the large machines built for modern factories.

Coal

13/25 Push an image to enlarge

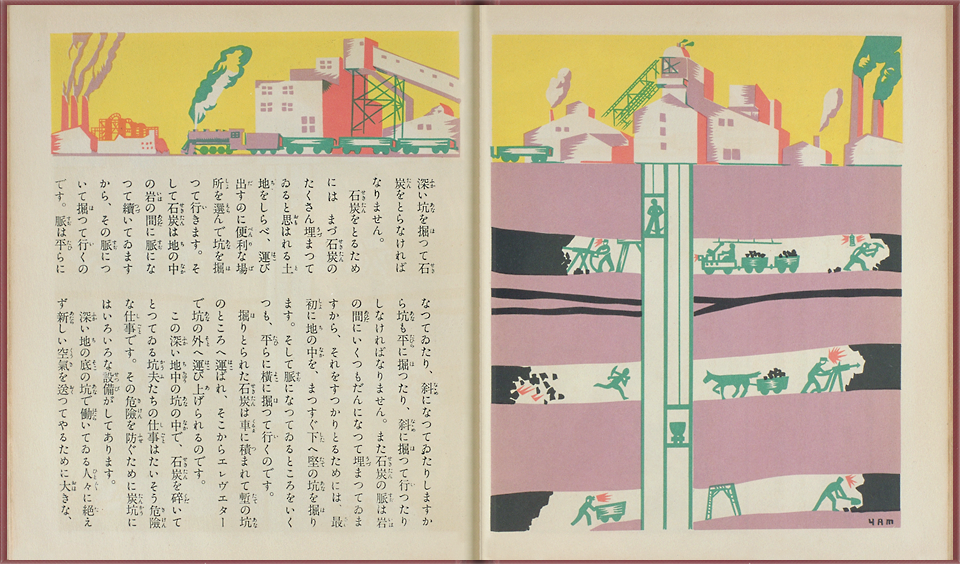

(♪) Coal Mines. As explained at the beginning of this book, coal is a substance formed through the changes in the earth’s crust over a very, very long period of time and is usually buried deep in the earth. To obtain this valuable resource, therefore, people devised many different methods. The right-hand page shows how a mine shaft would be dug straight down into the earth. From that shaft, horizontal shafts would be dug to follow the veins of coal found radiating out from the vertical shaft. The coal that was dug out was transported in cars and lifted by elevator to the surface. In the second level, as you can see, a horse was even used to pull the cars filled with coal through the shaft.

Coal

14/25 Push an image to enlarge

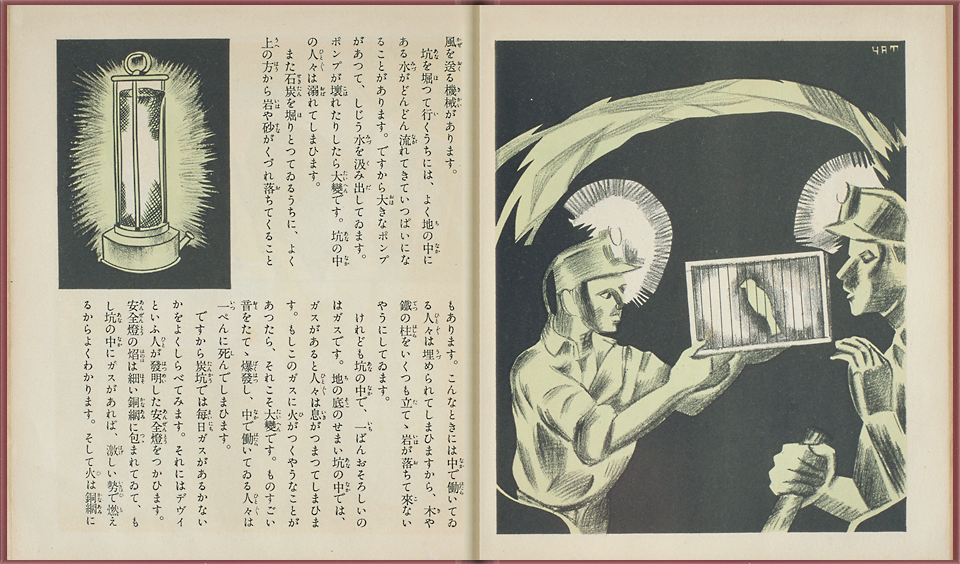

(♪) The people working deep in the earth in the coal mines faced many different dangers. This section explains the various safety methods they used. There were ventilating fans designed to send fresh air into the shafts. Drainage pumps were used to pump out water that accumulated in the pits. Steel posts and beams were used to buttress the walls of the shafts. The release of pockets of methane gas in the digging for coal was another source of danger, for it could poison the air of the miners or cause explosions. As methods of warning, the text mentions the special Davy safety lamps and the use of caged canaries, which were highly sensitive to the gas, to test the air before going to work. The most important factor in safety, however, was teamwork, as described on the following pages.

Coal

15/25 Push an image to enlarge

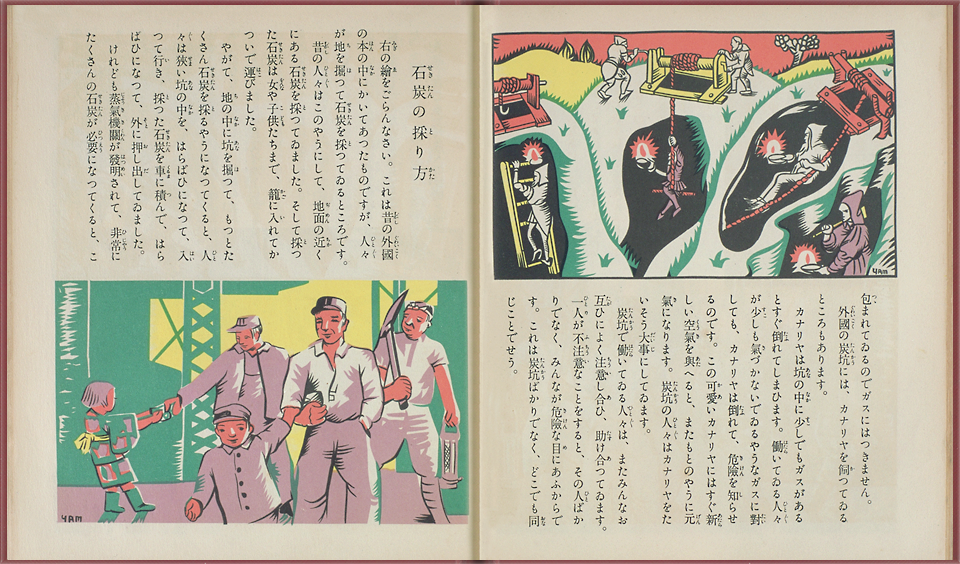

(♪) How Coal Was Mined. The illustration on the right page shows a picture of coal mining from an old document in Europe. The coal contained in layers of the earth fairly close to the surface is being brought up by human power alone. From the time of the industrial revolution onward, however, especially after the invention of the steam engine, such small-scale mining did not yield nearly enough coal. It was around that time that modern methods of coal mining began to be developed.

Coal

16/25 Push an image to enlarge

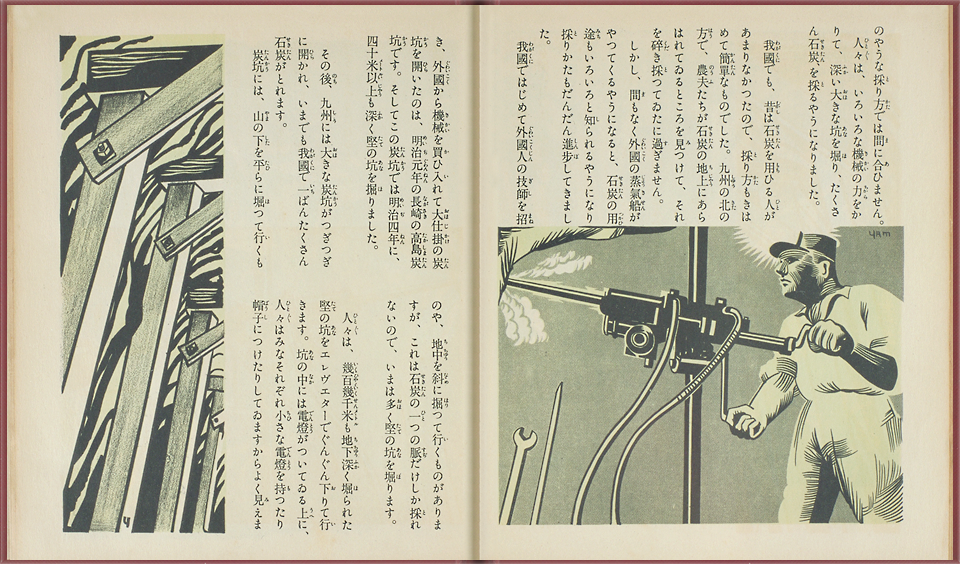

(♪) The first coal mine developed in Japan, at the beginning of the Meiji era (1868-1912), was the Takashima mine in Nagasaki prefecture. From then on, in order to hasten the modernization process, the Meiji government actively introduced foreign technology and coal mines were opened up in many parts of the country. Naturally the coal mines were eager to introduce the use of machines. The picture at right shows a man using a pneumatic drill to dig coal at the coal surface. The picture at left shows the prop beams used to prevent the walls of the shafts from collapsing.

Coal

17/25 Push an image to enlarge

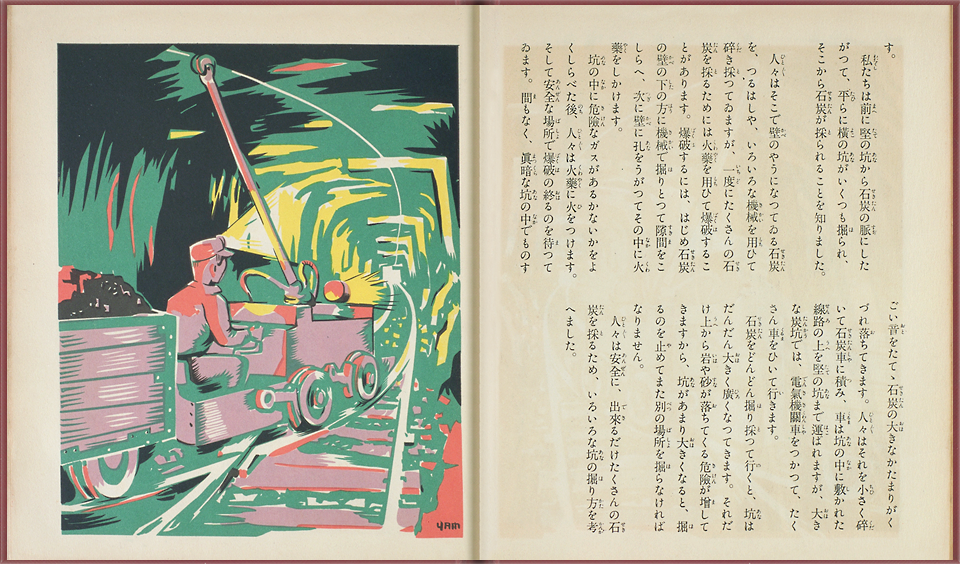

(♪) In Japan, unlike in other countries, coal is found mainly very deep beneath the earth’s surface. The vertical shafts of the mines, therefore, were often thousands of meters deep. The miners moved up and down using elevators and hauled the coal in cars along the shafts. Often in order to mine large amounts of coal more quickly, explosives were used. Toiling in the shafts despite the dangerous conditions and using machines to their greatest potential, the miners increased their output as much as possible. The illustration on the left shows a train for carrying coal out of a mine.

Coal

18/25 Push an image to enlarge

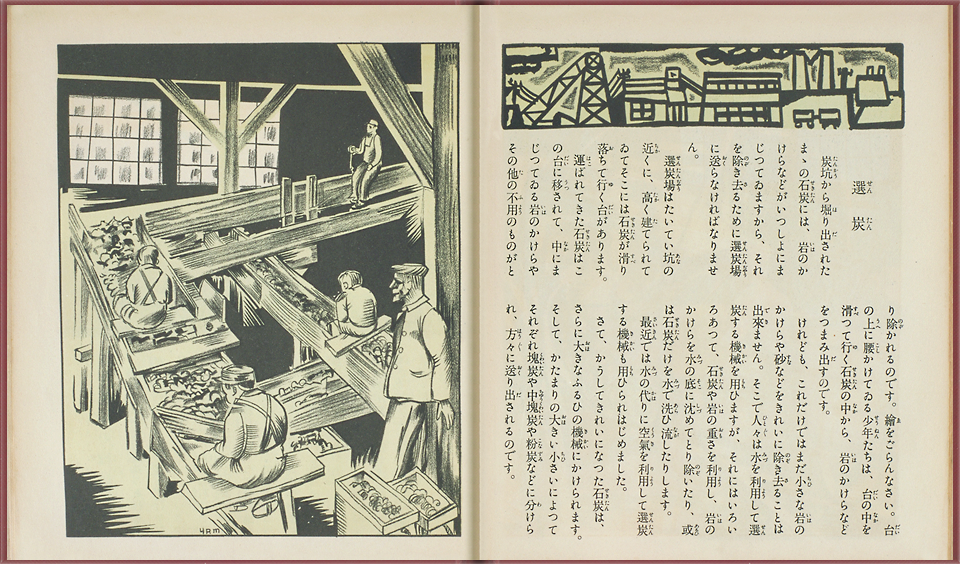

(♪) Coal Cleaning. This section explains how the coal was cleaned. The coal that was dug out was often mixed with other rocks and rubble that had to be removed. The picture at left shows a coal cleaning shop, probably a sketch based on documents from other countries. Men are supervising a number of young boys whose job it was to sort the rubble out of the coal. It makes a kind of pitiful scene. It was not long until the coal cleaning process was taken care of using air- and water-powered machines.

Coal

19/25 Push an image to enlarge

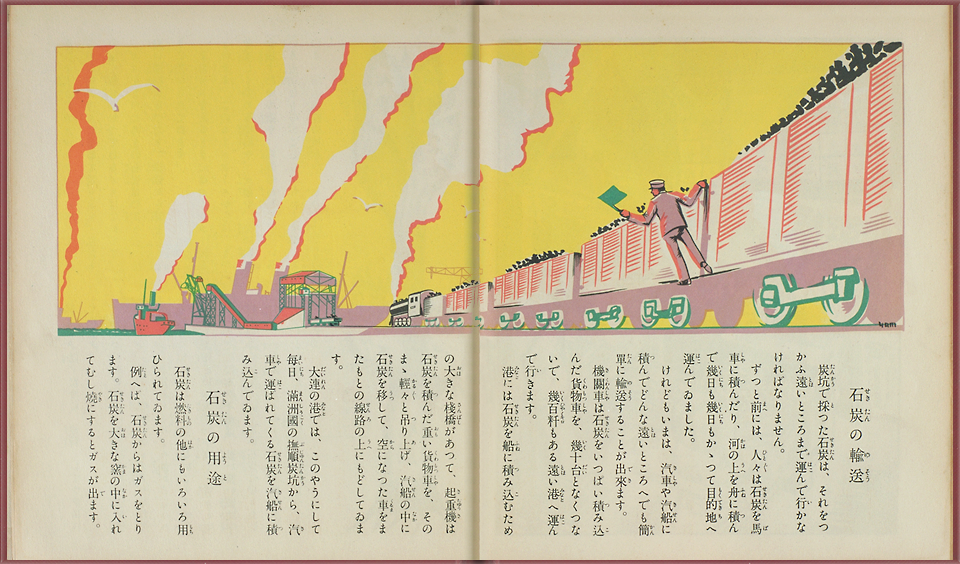

(♪) Transport of Coal. The coal ready for shipping was transported by wagon and ship in the early days, but by modern times, it came to be moved mainly by rail and ship. Countless coal cars piled high are snaking along the railway toward the port, where the coal is loaded onto steamships. As you can see, smoke is billowing from the steam engines of the train and the ship. Today we might be worried about air pollution from the fumes, but in the times when this book was made, billowing smokestacks were a symbol of prosperity. The text mentions “Manchukuo” was Japan’s name for the northeastern part of China, which was under Japanese control at the time the book was written. This, too, is part of a regrettable stage of history.

Coal

20/25 Push an image to enlarge

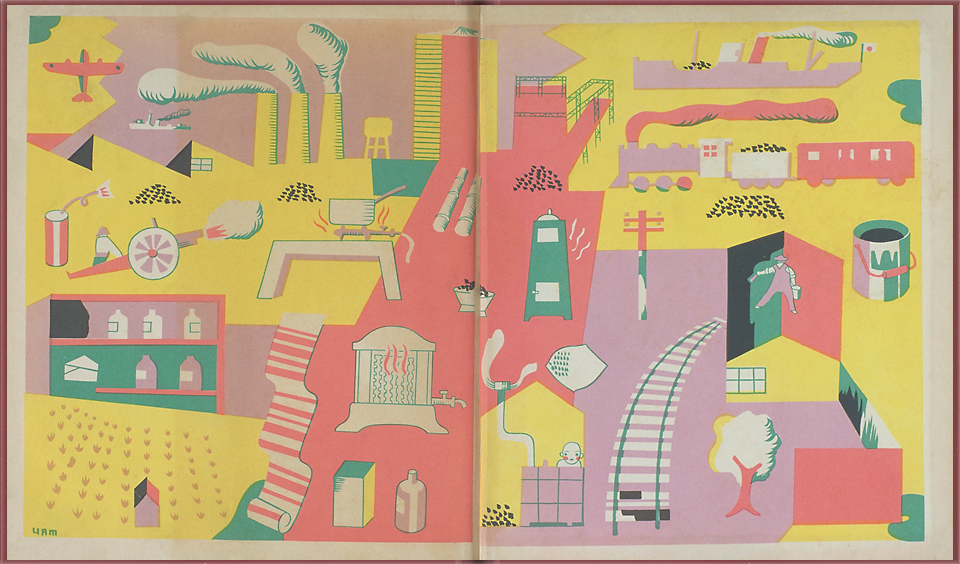

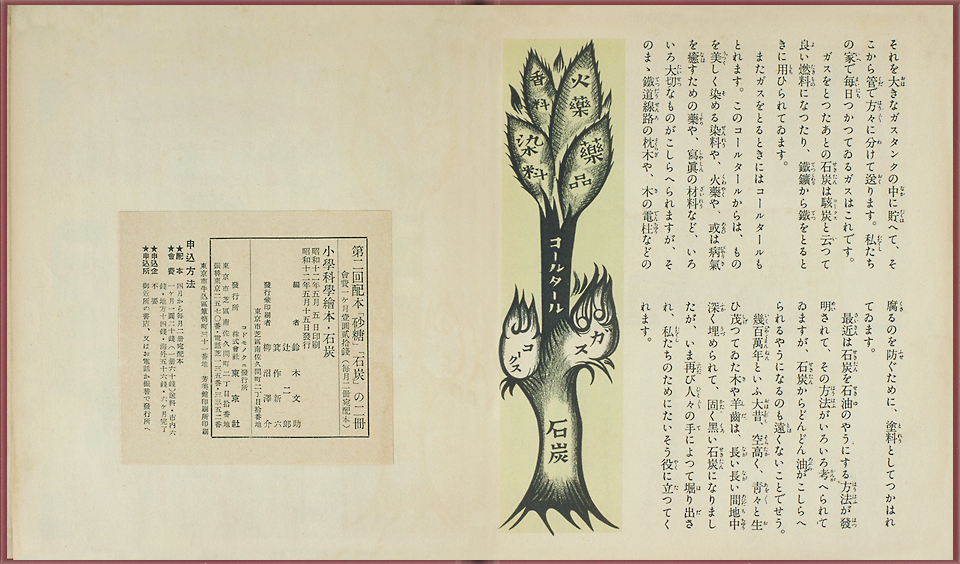

(♪) Uses of Coal. The story ends with an explanation of the various uses of coal. Starting from coal at the bottom, we can see how it was used to produce many kinds of products, from coal gas, coke, and coal tar, to chemicals, dyes, perfumes, gunpowder, and so on.

(♪) Colophon. This book was published in May 1937. This was just two months before the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, which triggered the start of the war between China and Japan. It was a time when the value of coal and oil as sources for the energy of industry was a matter of utmost concern. And yet this book does not give a sense of obsession with energy resources. It explains how human beings benefit from the earth’s precious resources and has the quality of a book conscientiously devoted to passing on basic and accurate knowledge about the subject to children. The value of this picture book can been seen in this quality.

(♪) Colophon. This book was published in May 1937. This was just two months before the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, which triggered the start of the war between China and Japan. It was a time when the value of coal and oil as sources for the energy of industry was a matter of utmost concern. And yet this book does not give a sense of obsession with energy resources. It explains how human beings benefit from the earth’s precious resources and has the quality of a book conscientiously devoted to passing on basic and accurate knowledge about the subject to children. The value of this picture book can been seen in this quality.

No narration on page 21

Coal

21/25 Push an image to enlarge

No narration on page 22

About the author 1/3

Compiled by MITSUKURI Shinroku (1893-1953)

Pictures by YAMASHITA Ken’ichi (dates unknown)\

1)

Tokyosha’s twelve-volume Elementary Science Picture Books is said to be the first science picture book series published in Japan. The subject-matter falls roughly into three categories: subterranean resources such as coal and iron, compiled by Mitsukuri Shinsaku, a science specialist, food commodities like rice and sugar, by agriculture specialist Suzuki Bunsuke, and airplanes, trains, and other forms of transportation by Tsuji Jiro, an engineering specialist. The names of the illustrators include leading names in avant-garde art movement during this time like Murayama Tomoyoshi and Natsukawa Hachiro (Yanase Masamu). This extraordinary nonfiction series helped children learn about topics that were a familiar and basic part of their daily lives from the scientific and cultural points of view.

22/25

No narration on page 23

About the author 2/3

2)

Compiler of this volume Mitsukuri Shinroku was a graduate in chemistry of the Tokyo Imperial University College of Engineering. He became professor at Tohoku University and later served as president and then advisor of a company in the chemical industry. He is also known for his prolific writing in the field of chemistry. In addition to Coal, Yamashita Ken’ichi also illustrated the Steam Ship and House volumes in the series. He was also active in book design and poster art. The end papers and the scenes of the port in this book remind us of the considerable influence of Soviet children’s books on artists in Japan in the 1920s.

23/25

No narration on page 24

About the author 3/3

3)

Critics from early on pointed to the influence of the Petersham books published in the United States on the Elementary Science Picture Book Series. Its year of publication, 1937, however, should be noted. With the February 26 attempted coup d’état by young military officers the previous year and the Marco Polo Bridge Incident the same year, Japan had already stepped into the mire of the Sino-Japanese War that would drag it into the Pacific War. Despite the political atmosphere in which it was published and the important theme of mining resources, Coal does not stoop to slogans about increasing energy production for the war but remains faithful to the mission of transmitting basic knowledge about resources from a scientific and cultural point of view. It is here that we may find the true significance of this book.

24/25

Contents

25/25